We sometimes refer to MacroFactor as an “adherence neutral” app, and you might be wondering what we mean when we use that term. So, this article will cover the topic as directly as possible, and discuss why we have an adherence-neutral philosophy.

Adherence refers to how closely someone sticks to their nutrition targets. It’s easy to say you want to be in an energy deficit and lose weight, but it’s considerably harder to actually stick to an energy deficit for a long enough period to successfully meet your weight loss goals.

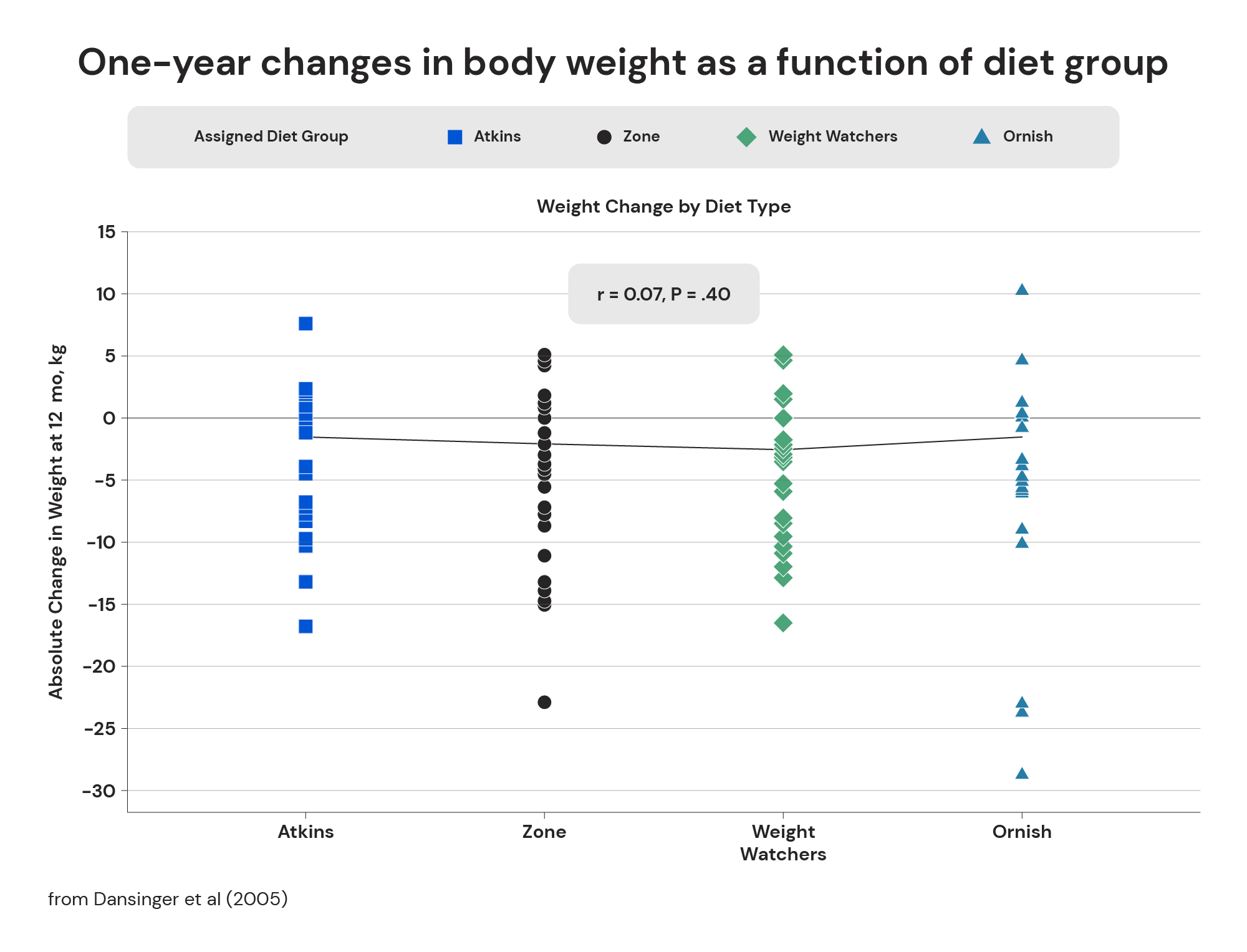

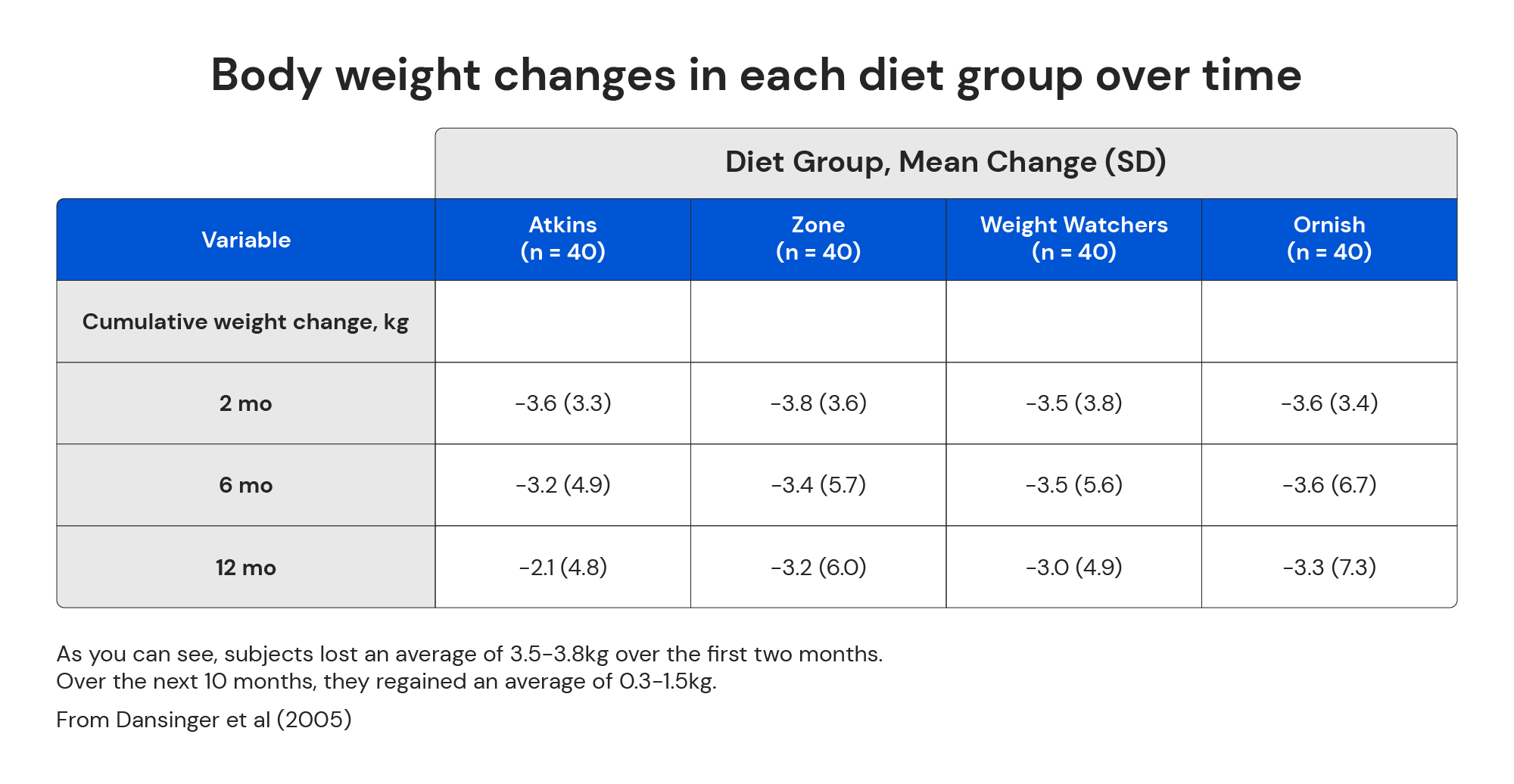

Unsurprisingly, dietary adherence is a strong predictor of successful weight loss. A seminal 2005 study by Dansinger and colleagues illustrates this point beautifully. 160 subjects were randomized into four groups following very different diets (Atkins, Zone, Weight Watchers, and Ornish) for one year. For the first two months, they were instructed to follow their assigned diet “to the best of their ability.” For the next ten months, they were encouraged to “follow their assigned diet according to their own self-determined interest level.”

At the end of the year, subjects in each group lost about 2-3.5kg, on average. All four diets seemed to promote similar amounts of weight loss.

However, on a group level, all of the weight loss occurred within the first two months; for the last 10 months of the year, subjects actually gained a small amount of weight.

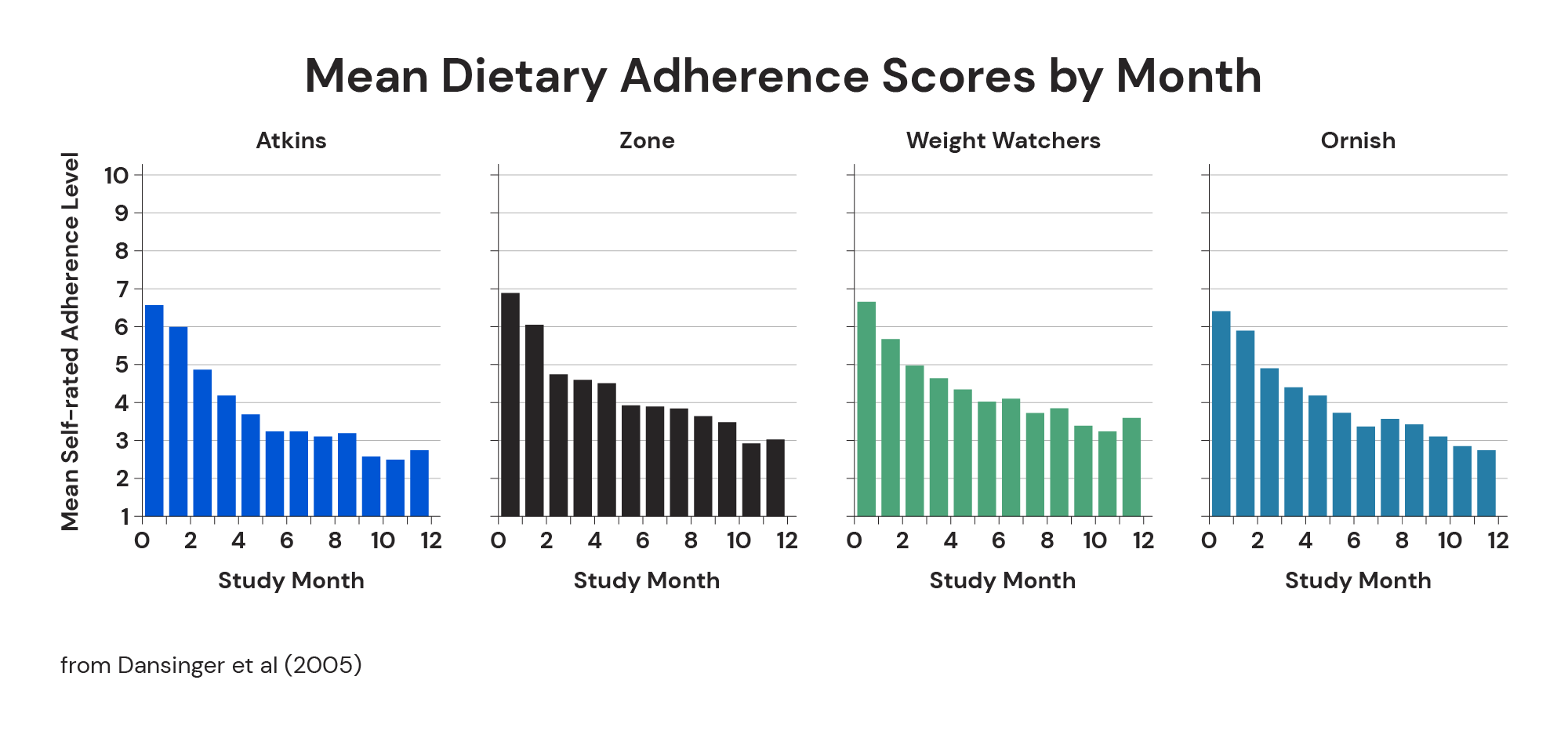

This decrease in weight loss success coincided with worse dietary adherence on a group level – for the first two months, dietary adherence was rated to be about 6-7 (on a 10-point scale, where 10 denotes perfect adherence), but by the end of the year, average dietary adherence had dropped to a rating of about 2-4.

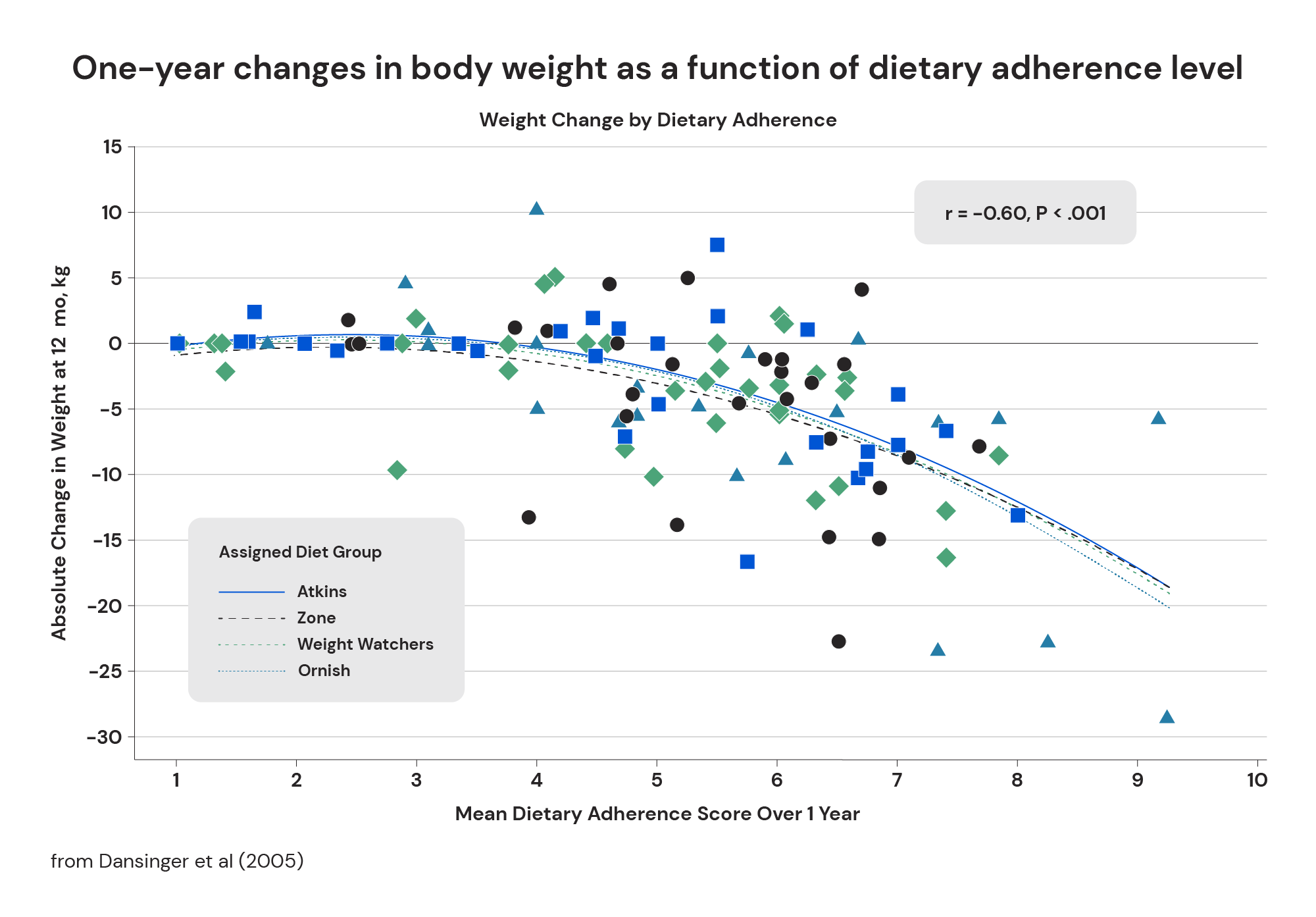

Furthermore, individual adherence to the assigned diet was strongly predictive of weight loss success – subjects in all four diet groups lost considerably more weight if their dietary adherence was higher.

Subsequent research on the topic has had broadly similar findings: dietary adherence is an absolutely critical factor of weight loss success. For what it’s worth, I’m sure that dietary adherence is similarly important for weight gain and weight maintenance, but it’s mostly been studied in a weight loss context.

So, with that context established, what does it mean to be “adherence neutral?”

Adherence neutrality refers to a lack of functional and visual elements within MacroFactor that would attempt to cajole people into adhering to their diet, or that would shame people for not adhering to their diet. Basically, nothing about MacroFactor will tell you that you’re doing something bad if you don’t adhere to your diet, and nothing about MacroFactor’s coaching functionality will work differently if you don’t adhere to your diet.

Since adherence is so important for reaching your dietary goals, our adherence-neutral philosophy might seem a bit confusing at first. So, this article will attempt to clear up that confusion, and explain why an adherence-neutral philosophy actually increases the likelihood that you’ll reach your goals.

This adherence-neutral philosophy primarily shows up two ways in MacroFactor: a lack of shame-based visual elements when someone eats a “bad” food or exceeds their calorie or macronutrient targets, and a lack of coaching elements that would attempt to make people “compensate” for not sticking to their dietary targets.

Neutral design

Unlike many nutrition apps, MacroFactor won’t provide negative feedback if you eat foods that are algorithmically determined to be “bad” (typically foods high in sugar or saturated fat), or if you exceed your calorie or macronutrient allotments for the day or week. These negative, shame-based visual elements show up in different ways in different apps, but they’re pretty pervasive. Maybe the numbers denoting your calorie intake for the day turn red if you exceed your calorie target. Maybe foods will be labeled with smiley faces or frowny faces based on whether an app deems them to be “good” or “bad” foods. Maybe a warning will pop up on screen if you’re about to log a food that would put you over your calorie target for the day, or if you’re about to log a food that’s high in sugar or sodium or saturated fat.

You won’t find any of that in MacroFactor.

At first, that may seem counterintuitive. If adherence is so important for dietary success, why wouldn’t MacroFactor forcefully alert people if they’re not adhering to their nutrition targets, or if they’re eating foods that aren’t in keeping with their dietary goals?

On the most basic level, these visual elements are almost never particularly informative. If eating something puts you over your calorie target for the day, that will be obvious to people that know how numbers work. You’ll see your calorie target for the day, you’ll see your calorie intake for the day, and it’ll be pretty easy to determine which number is bigger. You don’t need a warning or bold red number alerting you to that fact. Similarly, most people have a reasonable idea of good food choices – you don’t need a frowny face or pop-up warning to tell you that sugar-sweetened soda, bacon, or cake aren’t “diet food.”

These visual elements also simply wouldn’t be appropriate for a lot of MacroFactor users. They’re designed to cajole you into eating less or avoiding energy-dense foods, but not everyone is trying to lose weight. MacroFactor is a nutrition app, not solely a weight loss app, and plenty of people use it for the purpose of weight gain or weight maintenance. If you’re aiming to maintain your weight, being 100 calories above your calorie target isn’t inherently worse than being 100 calories below your calorie target. If you’re trying to gain weight, there’s certainly nothing wrong with exceeding your calorie target, and energy-dense foods may actually help you reach your nutritional goals.

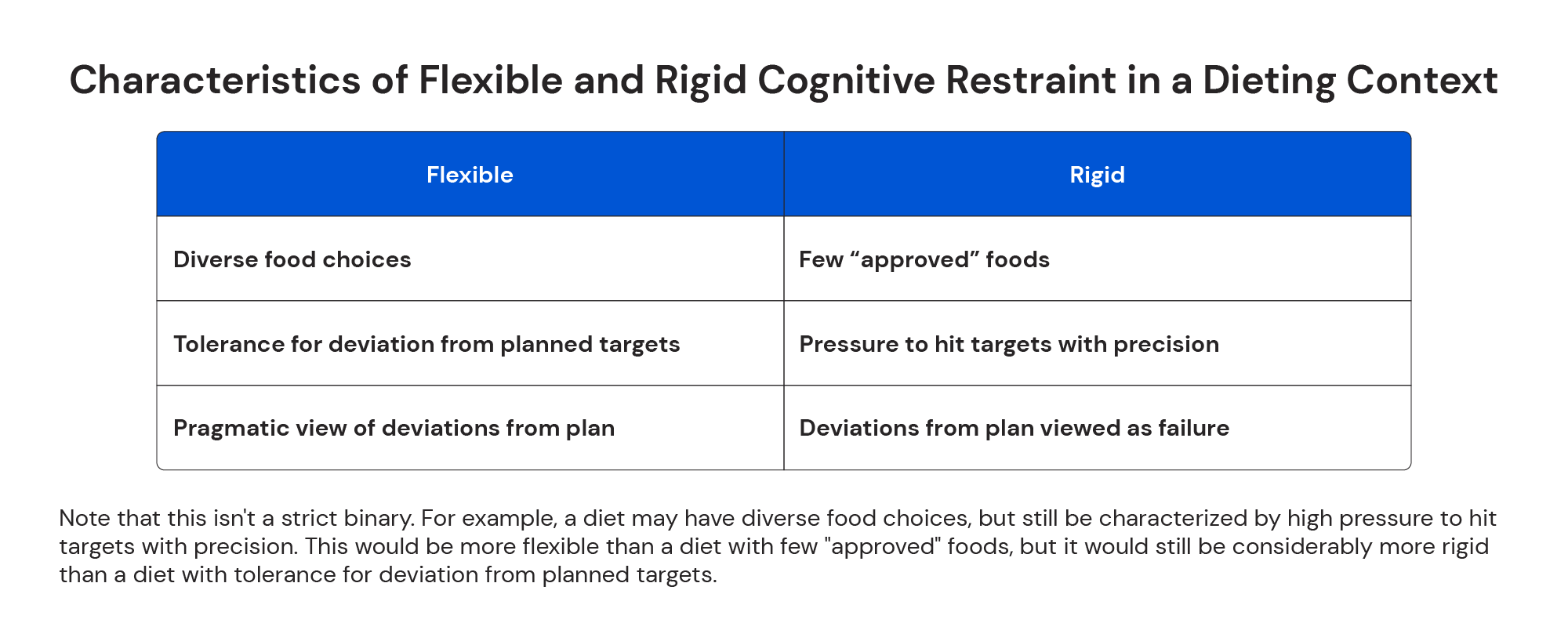

Furthermore, these elements can encourage binary thinking and rigid cognitive restraint, which are predictive of worse dietary adherence and long-term results. Flexible cognitive restraint, which is characterized by less black-and-white thinking about food choices and dietary adherence, is predictive of greater weight loss, healthier eating patterns, and better weight loss maintenance (one, two, three, four). In essence, people who rigidly view foods as either “good” or “bad,” or treat dietary adherence as a binary determination of being “on diet” or “off diet,” tend to struggle with reaching their dietary goals and maintaining their results. With this sort of rigid mindset, you’re either succeeding or failing – if you only eat “good” foods and perfectly hit your dietary intake targets, you’re succeeding; if you “slip up” and eat “bad” foods, or stray at all from your dietary targets, you’re failing.

That type of thinking can lead to both short-term and long-term problems.

Short term, a binary view of foods and dietary adherence – good foods vs. bad foods, adherent vs. non-adherent – can actually encourage worse dietary adherence, as previously mentioned. Once you’ve already classified a day as a failure (because you ate something “bad,” or exceeded your energy or nutrient targets for the day), your categorical assessment of the day can’t get any worse, so you may as well go for broke. One cookie turns into 10 cookies, or you end up exceeding your calorie target by 2000 calories instead of 100 calories.

Medium term, this binary view of foods and dietary adherence can sap your motivation. If you start classifying too many days as failures, it starts being easier to view yourself as a failure (at least when it comes to sticking to a diet). You begin losing self-efficacy, and start wondering if you’re even capable of sticking to a diet. As your motivation wanes, you start having more “bad” days, which further saps your motivation, and further reduces your self-efficacy, until you finally decide to give up altogether. This is termed “motivational collapse” – if you’d like a more in-depth treatment of the topic, you might enjoy this article.

Long term, a binary view of foods and dietary adherence makes it more difficult to maintain the results that you do achieve. Plenty of people have lost plenty of weight by eschewing certain foods or entire food groups, or by perfectly sticking to calorie and macronutrient targets for weeks or months at a time, but very few of those people maintain their results long term. For some people, applying rigid restraint can work for achieving short-term goals, but very few people want to avoid all indulgent foods, or stick perfectly to rigid dietary targets for the rest of their lives. So, once they reach their goal, they haven’t developed the skills that will help them maintain their results with a more relaxed and sustainable approach to eating. This increases the likelihood of weight regain and yo-yo dieting.

Since rigid, binary thinking leads to worse dietary adherence, and less long-term dietary success, we don’t think it makes sense to include visual elements in MacroFactor that encourage rigid, binary thinking by telling you (or strongly suggesting) that some foods are good and some foods are bad, or that you’ve failed by exceeding your calorie or nutrient targets for the day.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, those negative visual elements can create feelings of shame and guilt in many people (in some instances, they seem to be designed to cause shame and guilt). They’re an indication that you’ve done something wrong, and you should feel bad about it so that you won’t eat “bad” foods or exceed your calorie targets in the future.

That may not immediately raise any red flags for you. In fact, it may seem normal. Shame- and guilt-based messaging is pervasive in the world of weight loss (and in fitness, nutrition, and exercise content more broadly). After all, if you make someone feel bad about themselves, or bad about an action they’ve taken, they’ll be more likely to make a change, stick to a diet and exercise plan, and accomplish their weight loss goals in order to alleviate those negative feelings … right? It’s rarely articulated directly, but that’s the logic underpinning a lot of the marketing, content, and interventions related to weight loss.

This line of thinking is pervasive, but it’s dead wrong.

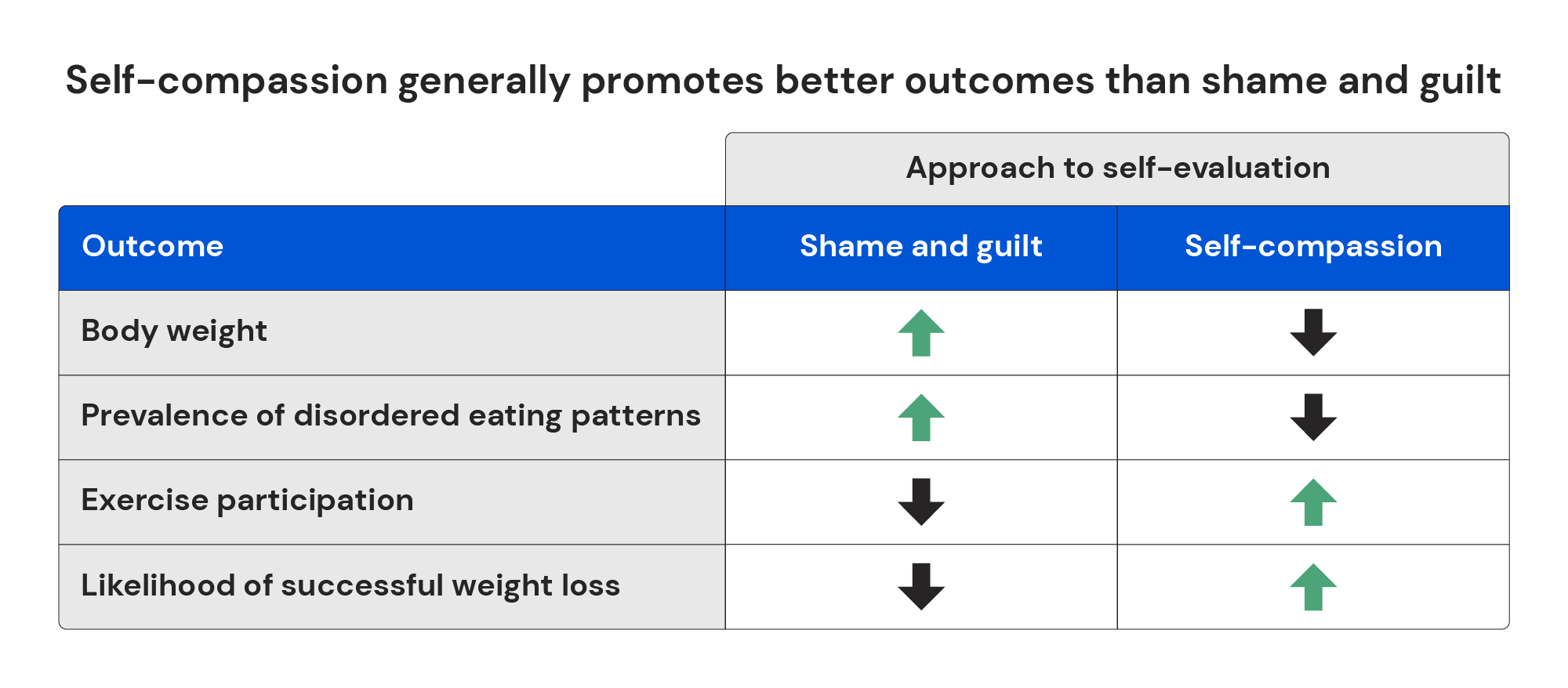

Research consistently finds that feelings of shame and guilt (and social experiences that are likely to create feelings of shame and guilt regarding one’s body) are predictive of higher body weight, more difficulty with weight loss, disordered eating patterns, and exercise avoidance (one, two, three, four, five, six, seven). Conversely, greater self-compassion is associated with better outcomes in all of these domains, and interventions designed to increase self-compassion also tend to have positive effects on eating behaviors, exercise participation, and weight management (one, two, three, four, five).

The positive results of intervention studies suggest that these aren’t mere associations: there appears to be a causal link between how people evaluate themselves (do they feel shame and guilt, or do they practice self-compassion?), and their eating behaviors, exercise habits, and weight loss success. Across the board, shame and guilt promote worse outcomes, while self-compassion promotes better outcomes.

So, on a purely ideological and philosophical level, we’re not in favor of shaming people for the food and nutrition choices they make. In a vacuum, if we have the choice between making someone feel bad and not making someone feel bad, we think it’s better to opt for not making people feel bad. But, on a purely functional and scientific level, shaming people for not adhering to their diet is unlikely to increase their dietary adherence. On the contrary, the research suggests that shaming people for not adhering to their diet will make them less likely to adhere to their diet moving forward.

Avoiding shame-based messaging and visual elements also comes with a functional benefit: it makes people more likely to actually log everything they eat. This provides users with a more accurate picture of their dietary habits, and it ensures that MacroFactor’s coaching algorithms will be making recommendations based on more accurate data.

In apps with shame-based messaging and visual elements, it’s not uncommon for users to stop logging for the day when they exceed their calorie target. Their app tells them the day is already a failure, so why keep logging food to just keep receiving more and more negative feedback? Many dieters are already too hard on themselves, and they don’t need further negative feedback from an app that will only serve to amplify the feelings of shame and guilt they’re already experiencing.

Similarly, even when you’re dieting, there will probably be occasions where something matters to you more than your diet does – holidays, social events, celebrations, and family get-togethers with plenty of delicious food available. All of us eat purely for enjoyment from time to time, and you don’t need an app telling you that you’re doing something wrong by having the audacity to enjoy a slice of birthday cake or a hearty plate of food at a family barbecue, instead of maintaining a laser focus on your weight-loss goal 100% of the time. Warnings and red numbers are supposed to tell you when you’re deviating from your goals. But, even when you’re trying to lose weight, weight loss isn’t always the primary goal of every meal and every day of eating. So it’s not uncommon for people to avoid tracking days and meals when they are truly “off diet,” to avoid the (completely inappropriate) negative feedback they might receive from their app.

As a result, people wind up with a less accurate view of their energy intake, which can lead to frustration and confusion. If you stop tracking for the day when you exceed your calorie target, you fudge food entries to avoid the appearance of exceeding your calorie target, or you don’t track on days you know you’ll exceed your calorie target, you might severely underestimate your energy intake. This can push you in the direction of thinking that your metabolism is “damaged” or “broken,” or toward thinking that you’ll need to crash diet in order to make progress. With a more accurate view of your energy intake, it may become clear that more reasonable strategies are available to you (maybe cutting yourself off after two or three drinks, only having one plate of food at social events, or not grazing after you’re full).

So, to wrap up this section, MacroFactor’s broader adherence-neutral philosophy drives our adherence-neutral approach to design: We clearly present your data, without any red numbers, pop-ups, warnings, or visual elements that can promote feelings of shame and guilt or disincentivize accurate food logging. This promotes greater dietary adherence, gives you a higher likelihood of long-term success, and helps provide you with a more accurate understanding of your dietary intake.

I’ll readily admit that, to some readers, it may feel like I’m making a mountain out of a molehill. If you have high self-efficacy related to dieting, and little-to-no weight-related shame or guilt, it’s entirely possible that none of this affects you at all (either positively or negatively). However, I can’t count the number of users who’ve told us that these small design decisions were incredibly helpful for their psychological health, their relationship with food, and their ability to stick to their diet and reach their goals. For the most part, these were people who’d struggled with weight loss in the past, had low self-efficacy related to dieting, and who had dealt with a lot of shame and guilt related to their body size and their difficulties with weight loss. And, for everyone in the middle of those two extremes, I think you’ll be surprised at how much more pleasant food logging is when you aren’t hit with negative feedback every time you eat a cookie or slightly exceed your calorie target for the day.

Coaching designed for actual humans

In nearly any domain, good coaching starts with the understanding that you need to meet the individual where they’re at, adapt to their needs, and keep moving forward even if the trainee isn’t always perfect.

Unfortunately, an alternative approach is common with nutrition coaching. With nutrition coaching, it’s not uncommon for a coach to give you a fixed diet (or a set of macronutrient targets) that you’re expected to perfectly adhere to. If you’re not making progress toward your goals, but you’re not perfectly adhering to your diet, you’re out of luck. Your coach will just tell you to try to perfectly stick to your diet next week. If any adjustments need to be made, your coach won’t make them unless you’ve been perfectly sticking to your diet.

The stated logic behind this approach is that the coach needs to assess whether their current recommendations are producing the desired results, before adjusting their recommendations. So, if you don’t follow the coach’s recommendations to a T, there’s no way for the coach to evaluate whether their recommendations are appropriate or not. Therefore, it’s your responsibility to perfectly follow the coach’s recommendations, so that they will have the necessary feedback to inform future adjustments.

If I were being cynical, I’d posit that the actual logic behind this approach is that it minimizes the time the coach has to invest in each client each week, which allows them to maintain a huge coaching roster, only work 10 hours per week, and make bank. But, I’m not a cynic, so I’d never suggest such a thing.

There are numerous problems with this approach, but one of the main issues is that perfect dietary adherence simply isn’t required for a coach to glean valuable feedback that can inform program adjustments.

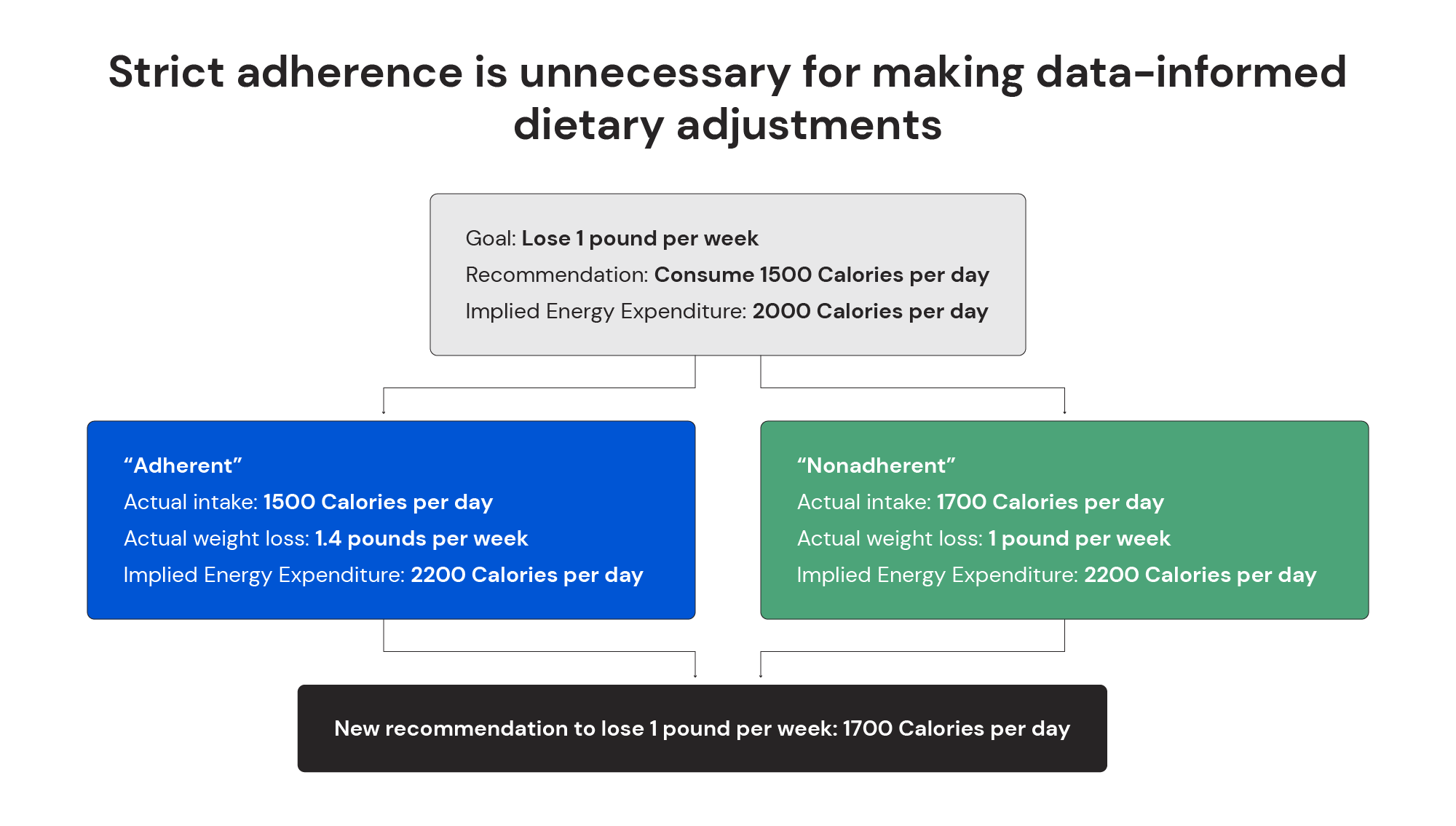

Just to illustrate, let’s say you’re trying to lose a pound per week, and you’ve been instructed to aim for an intake of 1500 calories per day. With a pretty low calorie target, you might struggle to perfectly adhere to your diet, and you wind up consuming an average of 1700 calories per day.

A bad coach might look at that, and just say that you did a poor job with dietary adherence, and you need to achieve an intake of 1500 calories per day for at least 2-3 weeks before they can assess your program and make adjustments.

A better coach would still be interested in how your weight responded to an intake of 1700 calories per day. Maybe you still lost a pound while consuming an average of 1700 calories. So, instead of just telling you to be more adherent, this coach would realize that your prior intake target of 1500 calories per day may have been a bit too low; you struggled with adherence because you were in a larger energy deficit than was intended, and you can achieve your goal of losing a pound per week with a higher intake target. So, instead of forcing you to try to achieve an intake of 1500 calories per day for a couple weeks before making any adjustments, they might go ahead and increase your intake target to 1600-1700 calories per day.

Ultimately, adherence isn’t necessary for determining whether someone’s calorie targets are appropriate for their goals. A strict adherence requirement just makes the adjustment process easier for a lazy coach. They can run through a simple decision tree that will only take a couple of minutes per client per week: Did you perfectly stick to your diet? If you didn’t, it’s your fault for being non-adherent, and you just need to adhere better next week. If you did, then the coach just needs to compare your rate of weight change to your target. If you’re losing weight slower (or gaining weight faster) than desired, your calorie target goes down. If you’re losing weight faster (or gaining weight slower) than desired, your calorie target goes up.

However, your weight and energy intake data will contain the same information and the same set of implications, even if you don’t perfectly adhere to your diet. In the illustration above, if you ate 1700 calories per day while losing a pound per week, that implies that … you can eat 1700 calories per day while losing a pound per week. It doesn’t matter that you were “supposed” to eat 1500 calories per day. However, if you did eat 1500 calories per day, you would have likely lost a bit more than a pound per week. So, if you were adherent, and lost weight a bit faster than your goal, a lazy coach would be able to see that result, and suggest that you increase your calorie target … probably to about 1600-1700 calories per day.

In the end, you get the same recommendations. But, the better coach’s recommendations are more responsive – you can get updated recommendations consistently, insead of being left on an island for weeks at a time if your adherence is less than perfect. Furthermore, it’s also less stressful to work with the better coach; they’re meeting you where you’re at and consistently providing you with valuable feedback, even if you’re not the model client (i.e. a fleshy robot who never strays from their nutrition goals) all the time.

That’s adherence-neutral coaching in a nutshell: Even if you don’t perfectly stick to your diet, your coach can still make timely, appropriate adjustments to help you continue pursuing your goals.

There are two main advantages of adherence-neutral coaching.

The first advantage relates to the concepts of rigid vs. flexible restraint, as discussed in the previous section.

With adherence-dependent coaching, you’re either adherent or you’re not – you’re “on diet” or “off diet.” It doesn’t just foster rigid restraint. It requires rigid restraint. Adherence-neutral coaching, on the other hand, fosters and allows for flexible cognitive restraint: You know that closely sticking to your dietary targets is likely to produce the best results, but you also have the leeway to deviate from those targets when you want to or need to, without missing out on valuable coaching feedback. I won’t dwell on this point, however, since I discussed the drawbacks of rigid restraint in the previous section.

The second advantage of adherence-neutral coaching is that it’s inherently more responsive and self-correcting if you do ever wind up with inappropriate recommendations.

Just to illustrate, maybe the perfect intake target for your goals is 2000 calories per day. But, for some reason (maybe your weight loss was masked by water retention for a period of several weeks), your coach recommended that you consume 1400 calories per day. Since that’s so far below your actual energy needs, you may have an extremely hard time adhering to that intake target for an extended period of time.

With adherence-dependent coaching, you’re basically out of luck. You’ll need to perfectly stick to this intake target of 1400 calories per day for at least a week or two before your coach will make any adjustments, even if your weight starts shooting down again. And, if you can’t perfectly adhere to an inappropriate intake recommendation for at least a week or two, you might be stuck with it for months (or, more realistically, until you either give up or switch coaches).

With adherence-neutral coaching, it’s no big deal. The scale can’t deviate from metabolic reality forever. Even if you don’t perfectly adhere to your intake target of 1400 calories per day, your rate of weight change will eventually reflect that, yes, you can eat considerably more than 1400 calories per day while pursuing your goal. So, your intake targets will increase to a more appropriate level, without ever requiring that you perfectly adhere to an inappropriate target for weeks at a time.

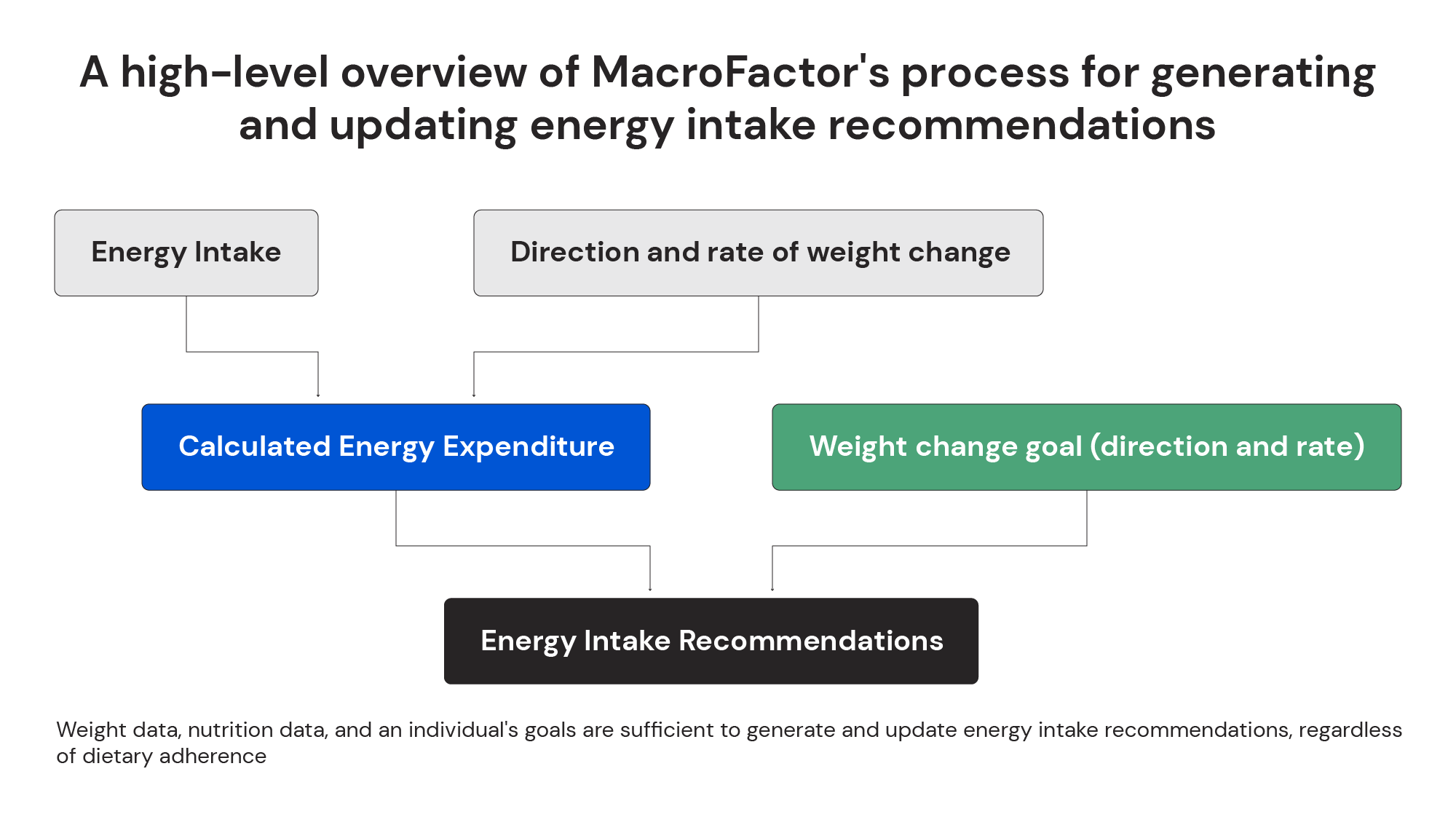

MacroFactor’s coaching functionality is based around its energy expenditure calculation, which is what allows MacroFactor’s coaching to be adherence-neutral. MacroFactor can estimate your energy expenditure based on your energy intake and rate of weight change, regardless of your goals or nutrition targets. The expenditure algorithm would work the same way, even if you didn’t have a goal or nutrition targets in the first place: The entire concept of adherence is irrelevant for the purpose of calculating your energy expenditure.

If you can calculate someone’s energy expenditure, you can calculate appropriate intake targets for their goals. Even if they don’t adhere to those intake targets, you can still provide a continuously updating estimate of their energy expenditure, as long as they reliably track their energy intake and body weight. So, you can still reliably adjust their intake targets to ensure the targets stay aligned with the individual’s goals, even if they have poor dietary adherence (for more on the advantages of estimating energy needs based on weight and nutrition data, you may enjoy these two articles).

Of course, adherence-neutral coaching doesn’t imply that dietary adherence is unimportant for achieving your goals. However, “adherence” isn’t a binary variable.

A flexible, adherence-neutral approach to dieting empowers the individual to consider their goals and priorities in order to make the best choices for themself. There may be times when your nutrition- and weight-related goals are your top priority, and so you aim to closely adhere to your intake targets. On the other hand, there will probably be situations (single meals, or even prolonged periods of time) where something else is a higher priority – enjoying a party or a holiday, getting through a stressful period in your life, etc. – so your nutrition- and weight-related goals take a back seat. You may want to know what you would need to eat to pursue your goals, but you’re less concerned with trying to be perfectly adherent (and you certainly don’t need to be shamed for being less than perfectly adherent).

An adherence-neutral coaching system also allows you to determine the definition of adherence that makes sense for you, instead of enforcing an arbitrary external standard.

If you compete in a sport that requires you to make weight on a certain day, you might need to be very strictly adherent to your dietary targets, and aim to be within 2-3% of your weekly calorie and macronutrient targets. A coaching system without strict adherence requirements doesn’t stop you from imposing strict adherence requirements upon yourself. However, since those strict adherence requirements are self-imposed, instead of being externally dictated, MacroFactor will still be able to suggest appropriate dietary adjustments if you ever fall short of your own idea of “perfect adherence.”

Conversely, you may be trying to lose a bit of weight, but it’s considerably more low-key, and there’s not a rigid end date. So, you might like to lose a pound per week, but you’re happy as long as the number on the scale is generally moving down. In that case, your idea of acceptable adherence might be to stay within ~300 calories of your calorie target, get reasonably close to your protein target, and not worry much (if any) about your fat and carbohydrate intake. An even higher level of adherence would be unnecessary for pursuing your goal in the manner you’re comfortable pursuing it.

Wrapping it up

To circle back to the start of this article, dietary adherence is crucially important for achieving your weight-related goals. However, attempting to shame people into being more adherent (or utilizing a coaching system that tries to force perfect adherence) can actually lead to worse adherence and worse results. An adherence-neutral approach doesn’t promote feelings of shame and guilt, and does promote flexible cognitive restraint, which will increase your likelihood of actually attaining high dietary adherence and achieving your goals.

Ultimately, we want MacroFactor to maximize the likelihood that you’ll achieve your goals and be able to maintain (or build upon) your results. We also want it to be able to flexibly adapt to your goals and lifestyle, and help you avoid any unnecessary stress, anxiety, or feelings of shame and guilt. Our adherence-neutral philosophy, which is reflected in MacroFactor’s design and its coaching system, is what allows us to pursue all of those aims, without compromising on any of them.