Around this time of the year, millions of people are setting new and ambitious goals to tackle in the new year ahead. Approximately one year ago, I published an article about how to set really effective goals, and how to make some small behavioral changes to facilitate the formation of more goal-compatible habits. That article provides a great starting point, but it’s missing two important things. Setting great goals and strategically building new habits is an excellent first step, but long-term success requires two more things: a comprehensive framework for understanding (and promoting) sustainable motivation, and a comprehensive framework for understanding (and promoting) sustainable behavior change. So, that’s exactly what we’ll cover in the current article, which is the unofficial “part 2” of last year’s article.

Why Focus on Behavior Change?

The weight loss research is intriguing – nearly everything works in the short term, yet very few things work in the long term. When we are in a caloric surplus (that is, consuming more calories than we burn), we store the extra calories as fat mass, which can accumulate over time. In contrast, a caloric deficit describes an energy shortfall; our energy expenditure exceeds our caloric intake, and we tap into our stored body fat to cover the difference. Research has shown that a wide variety of short-term dietary interventions can be used to establish a caloric deficit, which leads to a loss of fat mass over time. However, many of these interventions are quick fixes – interventions that are impractical, unsustainable, or simply insufficient for promoting a long-lasting change that facilitates successful long-term maintenance. As a result, the research largely reflects what we see and experience in the real world: short-term weight loss and weight regain cycles are the norm, while sustained long-term weight loss is less commonly observed.

We can apply any of the common “quick fixes” to establish a short-term deficit and see some weight loss progress. Cutting fat, cutting carbs, cutting sugar, you name it. In fact, some of the more restrictive approaches induce some of the quickest progress. However, that progress tends to be short-lived, ultimately leading to the next instance of weight regain. These frustrating cycles of weight loss and weight regain are common, but far from inevitable.

The problem is that these “quick fix” strategies lack the foundation and key characteristics that give a dietary change the staying power required to be a long-term solution. In order to facilitate long-term success, a dietary strategy must be built upon a foundation of motivation and behavior change, ultimately yielding an approach that is flexible, adaptable, empowering, self-reinforcing, and sustainable. This article will not give you the newest food-focused “quick fix” to kickstart your next short-term diet. Rather, it will discuss evidence-based tips for leveraging key concepts of motivation and behavior change to fuel your long-term success, while also highlighting how MacroFactor can provide support along the way. But before we get to all of that, let’s begin with a quick primer on evidence-based goal setting.

Goal Setting

If you haven’t read last year’s article on goal setting, I’d highly recommend checking it out. It provides a detailed and comprehensive look at how to set goals that are compatible with the best available evidence (that is, goals that are more likely to facilitate success, according to the best science available). Nonetheless, I’ll provide a more concise summary of the key points here, because goal setting is a foundational step that sets the stage for motivation and behavior change. Before we talk about cultivating motivation, we need to know what we’re getting motivated for.

In many industries (including fitness), “SMART” goals have become the accepted norm. In this context, “SMART” is an acronym; while there are differing definitions floating around, a common version is Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. A lot of people assume, likely due to the popularity of this concept within the fitness world, that the SMART goal framework was carefully designed and rigorously tested by scientists who were interested in helping people improve their health or fitness. In reality, SMART goals were designed to help managers keep their employees on task in a corporate setting, and some research suggests that they might even be a bit counterproductive for health and fitness applications.

A major shortcoming of the SMART goal paradigm is right in the name. The “R” is commonly said to represent “relevant,” which begs the question – relevant to what? This part of the acronym directly implies that the goal is set in relation to an external element, but the SMART goal approach fails to incorporate any such external elements or explicitly map out the “big picture” or broader context for the goal. The result is a cycle in which people set singular, de-contextualized SMART goals, run into challenges, switch goals, run into more challenges, and ultimately become discouraged.

But here’s the good news: there is a better way. A goal setting approach that is comprehensive, fully contextualized, and backed by science.

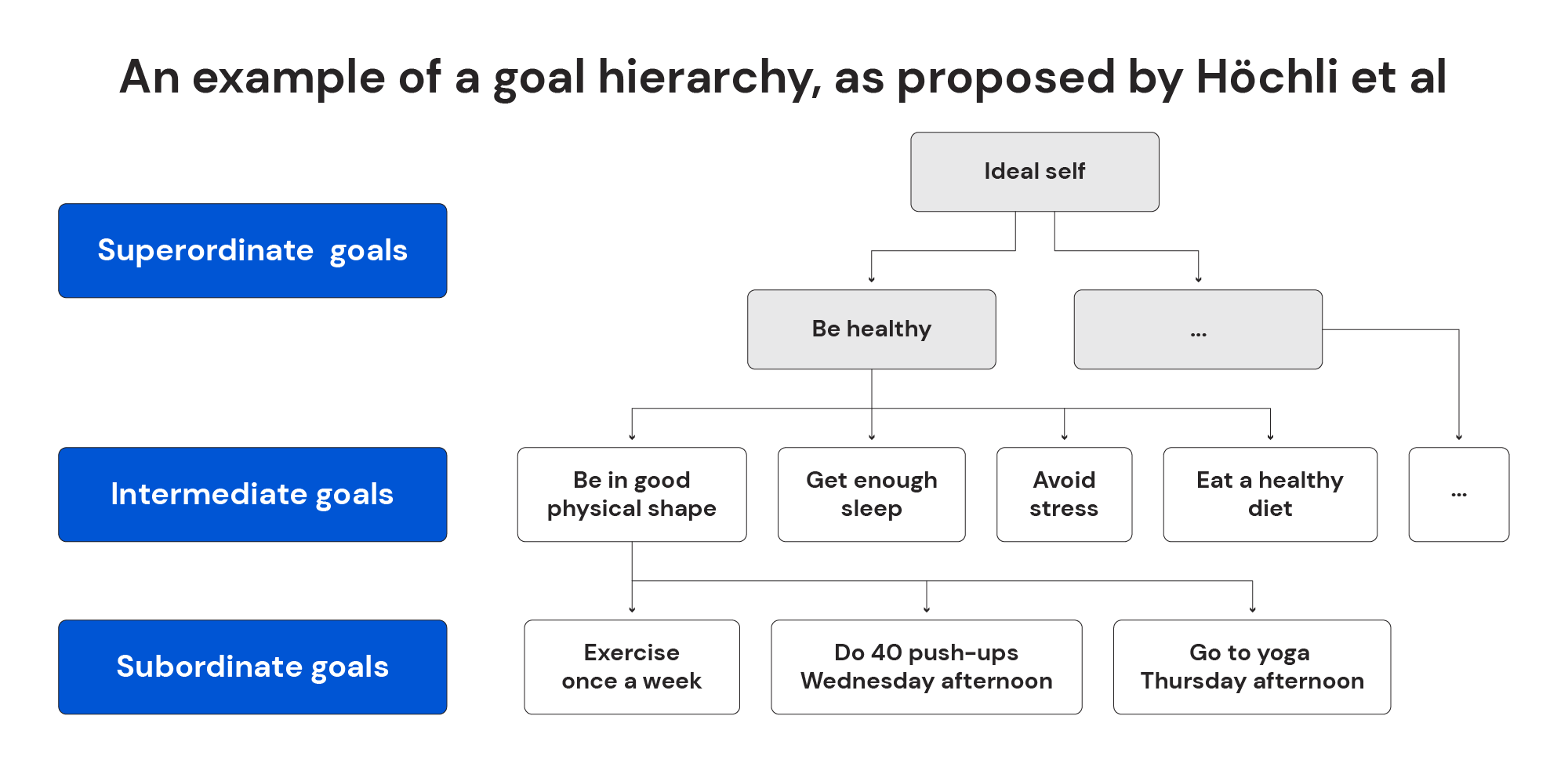

Rather than setting a small collection of disjointed or unconnected SMART goals, you’re much better off establishing a goal hierarchy, as described by Höchli et al. The central cornerstone that anchors a goal hierarchy is the superordinate goal. A superordinate goal refers to idealized, big-picture concepts of one’s self, and is more reminiscent of a value or an identity than a goal. It is a stable, durable, long-term goal that reflects one’s sense of self, which helps the goal hierarchy endure when friction or challenges arise.

The superordinate goal is supported by intermediate goals. These are less abstract, more specific, and provide a general direction that leads someone toward their superordinate goal. Intermediate goals are supported by subordinate goals, which look a lot more like the SMART goals that many people are accustomed to setting. Subordinate goals are precise goals that specify exactly what you’re going to do (and how you’re going to do it) in order to achieve your intermediate goals.

Figure 1 presents an example of a goal hierarchy, which was proposed by Höchli et al. The superordinate goal is to “be healthy.” This is an identity-based goal that reflects an individual’s values and idealized version of who they want to be. Their idealized form of self is a healthy person who does what healthy people do, and that idealized self is likely to persist for months or years because it reflects a core value.

Of course, being “a healthy person who does what healthy people do” is a bit vague. That’s where the intermediate goals come in. In this example, a “healthy person” might be in good physical shape, get enough sleep, avoid stress, and eat a healthy diet. That’s great, but how would one make tangible steps toward those outcomes?

That’s where the subordinate goals come into play. These are the highly specific goals that reflect day-to-day and week-to-week actions that are going to make the intermediate goals, and by extension the superordinate goal, a reality.

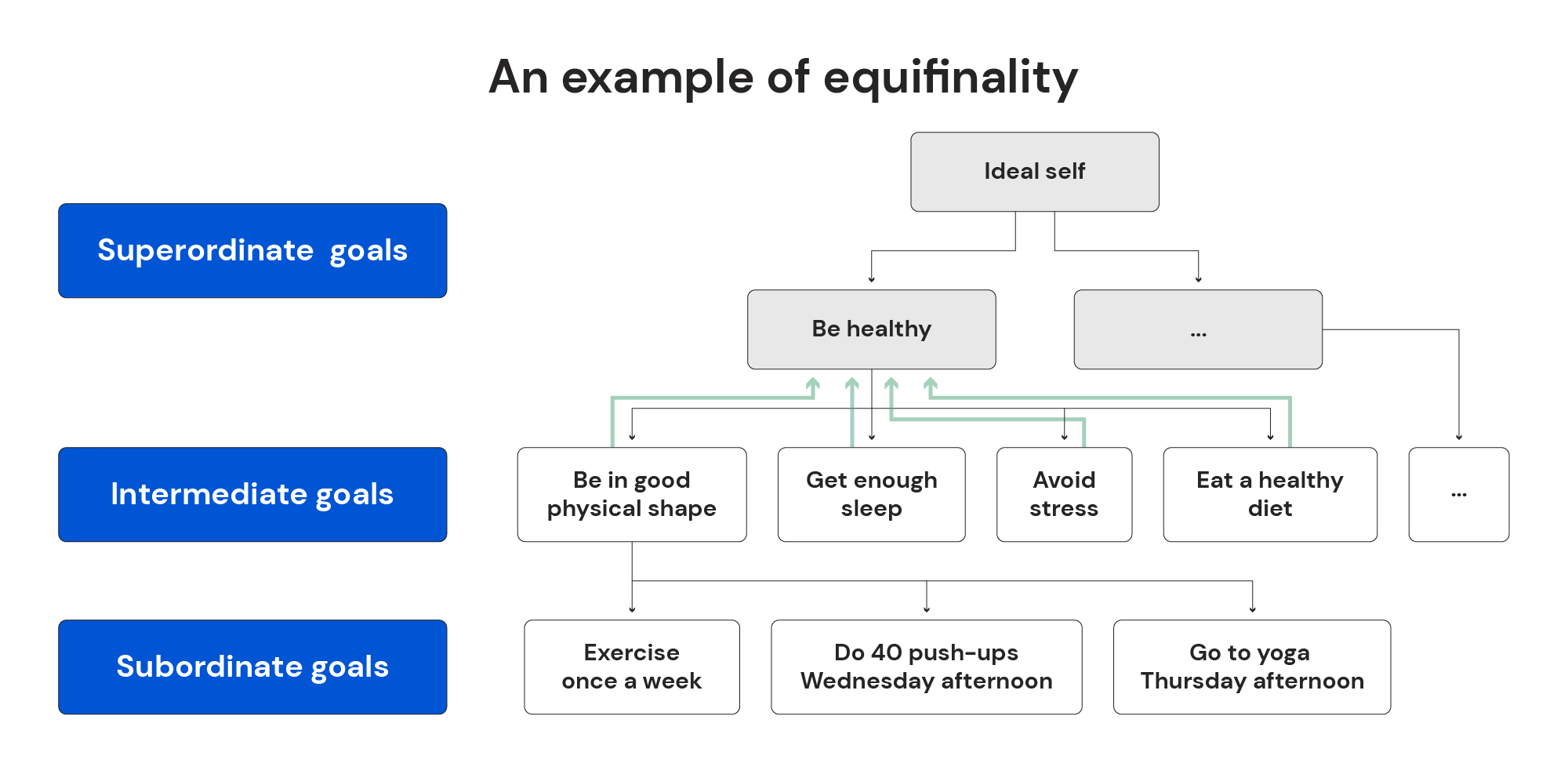

There are several major advantages of opting for a robust, comprehensive, and well-aligned goal hierarchy over a somewhat random assortment of SMART goals. As noted previously, the superordinate goal serves as an anchor that gives the goal striving process more stability and resiliency over time. In addition, goal hierarchies leverage something called “equifinality,” which means that multiple lower-level goals can support the exact same higher-level goal. For example (Figure 2), the superordinate goal of “be healthy” is simultaneously supported by several intermediate goals (be in good physical shape, get enough sleep, avoid stress, and eat a healthy diet). So, even if your exercise adherence slips a bit, you can still maintain positivity and motivation because you’re making other meaningful strides toward your higher-level goal by getting enough sleep, avoiding stress, and eating a healthy diet. These other successes keep motivation afloat so you can steady the ship and get your exercise habits back on track. Without equifinality, it’s quite possible that you could become very discouraged when your exercise adherence slips a bit – potentially discouraged enough to discontinue your goal striving process altogether.

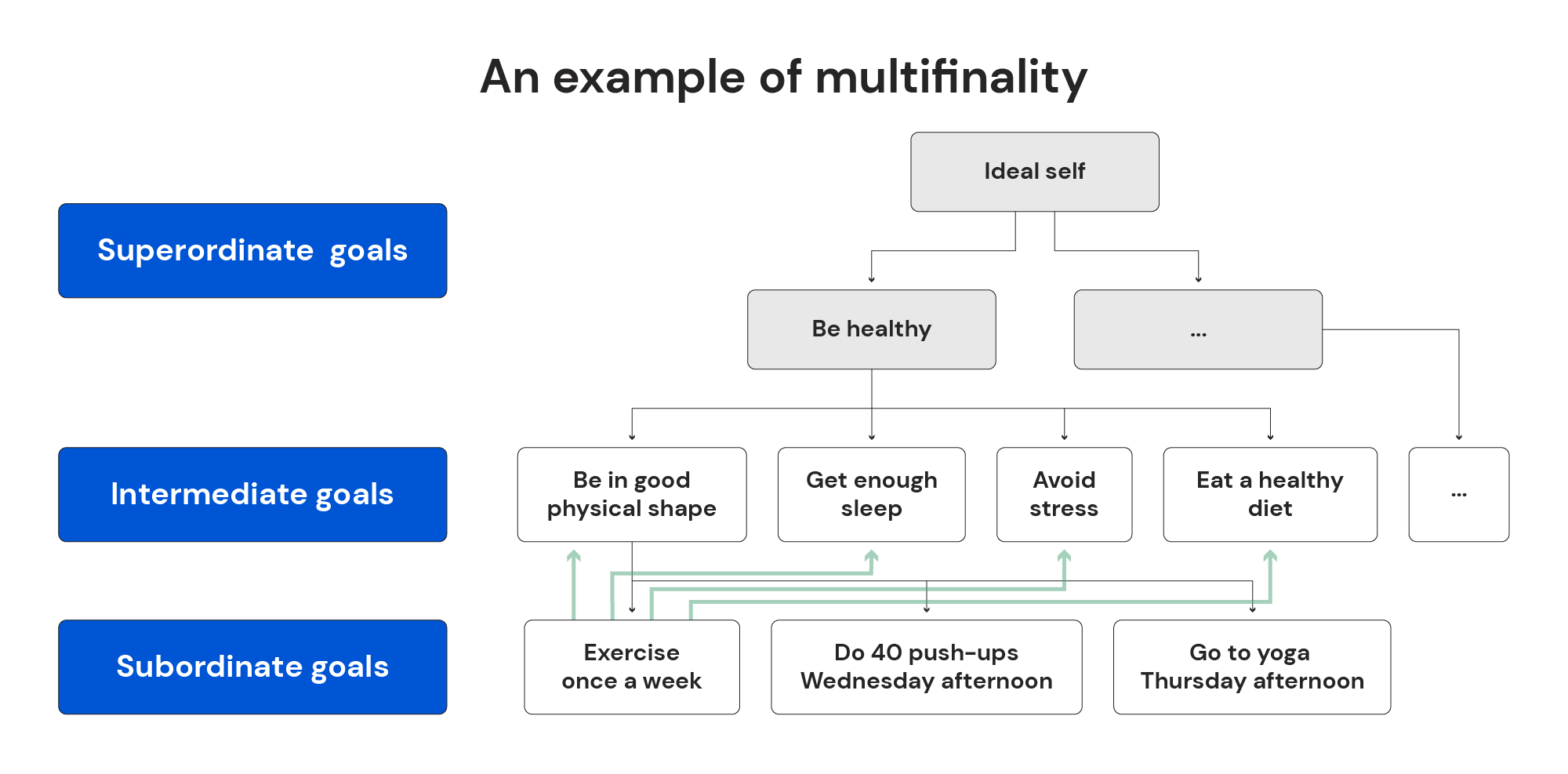

Goal hierarchies also leverage something called “multifinality,” which means that a single lower-level goal can support multiple higher-level goals. For example (Figure 3), regular exercise can certainly help someone be in good physical shape, but exercise has multifaceted effects. Many people notice improved sleep quality, better stress management, and better appetite regulation when they exercise on a regular basis. As a result, this one subordinate goal is simultaneously supporting several intermediate goals. This is important because it supports adherence to lower-level goals. When your alarm clock goes off on a cold January morning, it’s quite possible that you’d rather get an extra hour of sleep in a warm bed than get to the gym.

So what actually compels you to make the more goal-compatible choice to wake up and go to the gym instead of making the more comfortable choice to sleep in? Some days, it’s the desire to be in good physical shape. Other days, it’s because you know how poorly you sleep when you don’t exercise, how stressed you get when you don’t exercise, or how much extra snacking you do when you don’t exercise. Multifinality gives us more reasons to engage in the same activity, and on any given day, we only need one reason to be just good enough to get us out of bed.

In summary, a well-aligned goal hierarchy is highly advisable for anyone with goals pertaining to health or fitness. When filling in that goal hierarchy, there are a number of additional recommendations to keep in mind. For example, you want to emphasize approach goals (i.e., eat more vegetables) over avoidance goals (i.e., avoid high-calorie desserts). You want to emphasize goals that enable flexible cognitive restraint (i.e., consume fewer calories outside of structured meals) over goals that enforce rigid cognitive restraint (i.e., never eat snacks under any circumstances). You want to emphasize process goals (bench press twice per week) over outcome goals (increase my bench press by 20 pounds). You want to emphasize mastery goals (i.e., learn how to cook more macro-friendly dinners) over performance goals (i.e., place in the top 3 at a local cooking competition). Finally, you want to set goals that are hard enough to keep you excited and engaged, but easy enough to be feasible. We tend to lose interest when goals are way too easy, and we tend to lose confidence and motivation when goals are way too hard.

Note that these aren’t hard rules, but merely guidelines – a goal hierarchy has plenty of room for several different types of goals. Once you’ve got your goal hierarchy set up, the focus shifts to cultivating motivation to enthusiastically pursue those goals.

Motivation

From my perspective, there are two major misconceptions about motivation. The first is that motivation is a singular construct – you either have it or you don’t. The second is that motivation is actively generated – if you don’t have it, you have to manufacture it. My perspective is primarily shaped by self-determination theory, which is a theory of human motivation with a great deal of scientific support. In direct contrast to these misconceptions, self-determination theory posits two very different perspectives on motivation.

As for the first misconception, self-determination theory is predicated on the idea that motivation is not a singular construct. Instead, this theory suggests that several different types of motivation exist, and that they can be placed on a spectrum that spans from lowest quality to highest quality. In order to understand how it’s possible to rank motivation quality on a spectrum, we should check out some common definitions of motivation:

“Psychological energy directed at a particular goal” (source)

“The energizing of behavior in pursuit of a goal” (source)

“The process whereby goal-directed activities are initiated and sustained. In expectancy-value theory, motivation is a function of the expectation of success and perceived value” (source)

With this in mind, we can operationally define “higher quality motivation” as a form of motivation that more effectively drives us to initiate and sustain goal-directed behaviors.

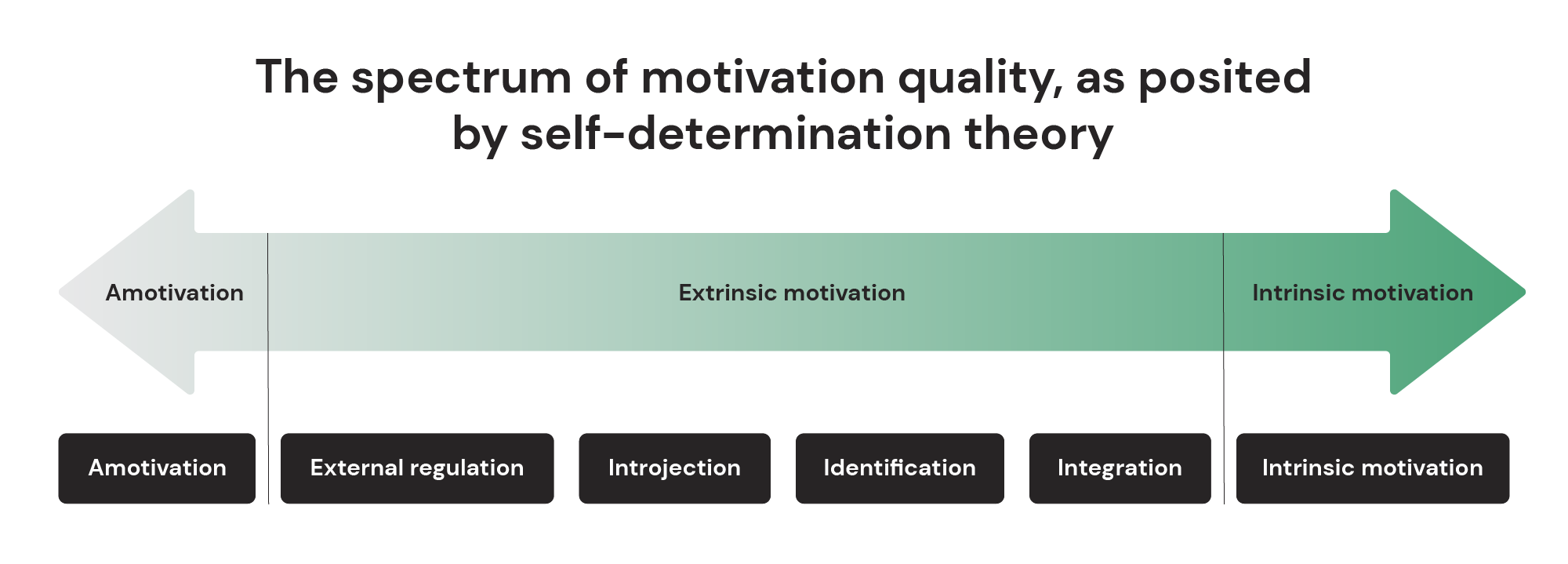

Within self-determination theory, it should be no surprise that the lowest form or quality of motivation is “amotivation,” or the complete absence of motivation. As you move from the lowest-quality form to the highest, there is one key characteristic that changes: the degree to which motivation is intrinsic versus extrinsic. As a result, purely intrinsic motivation represents the highest-quality form of motivation. The full spectrum of motivation types is presented in Figure 4.

As explained by Ryan and Deci:

The term extrinsic motivation refers to the performance of an activity in order to attain some separable outcome and, thus, contrasts with intrinsic motivation, which refers to doing an activity for the inherent satisfaction of the activity itself.

Notably, there are several different types of extrinsic motivation. To emphasize this point, Ryan and Deci lean on the example of a student doing homework. Some students might do it to avoid being punished by their teacher or parents. In contrast, some students might do it because they believe it will benefit their career. Neither scenario involves a student doing homework because they simply love doing homework; both scenarios involve extrinsic motivation. However, doing homework for the purpose of furthering one’s career reflects a higher level of motivation quality that involves “personal endorsement and a feeling of choice,” while doing homework to avoid punishment involves neither. So, both scenarios fall under the umbrella of extrinsic motivation, but one involves more internalized perceptions pertaining to the value, importance, and regulation of the activity.

Intrinsic motivation is the highest-quality form of motivation, according to self-determination theory. This involves completing an activity due to interest, enjoyment, or inherent satisfaction. It is a self-directed activity that the individual sees as valuable, important, and beneficial. They don’t need a coach, teacher, or parent to twist their arm in order to engage in the activity – they genuinely want to do it for its own sake.

That sounds great, but I know what you’re thinking – that’s easier said than done. How do we manufacture intrinsic motivation? That brings us to the second misconception, which is that motivation is actively generated. Self-determination theory posits a different idea entirely.

Psychological Needs Fulfillment

A foundational idea underpinning self-determination theory is that people naturally have a curiosity to try new things, master new challenges, and to integrate these experiences into a continuously updating sense of self. In other words, people have a desire for personal growth, and repeated instances of self-improvement, goal attainment, and skill mastery positively impact one’s sense of self. In ideal circumstances, people operate with a strong sense of self-determined motivation, meaning that they are making volitional choices and taking volitional actions that are motivated by their own desires and ambitions, and they truly feel like they have some degree of control over dictating their own path forward.

Framed differently, self-determination theory suggests that people have a tendency to pursue growth opportunities, such that we can view intrinsic motivation as a natural state that manifests itself under the right conditions and circumstances. So, we don’t need to manufacture intrinsic motivation. Rather, we need to create the conditions that allow it to manifest organically. Fortunately, the theory doesn’t end there – it gives us a playbook to facilitate the cultivation of intrinsic motivation, so we can actually put these concepts into action.

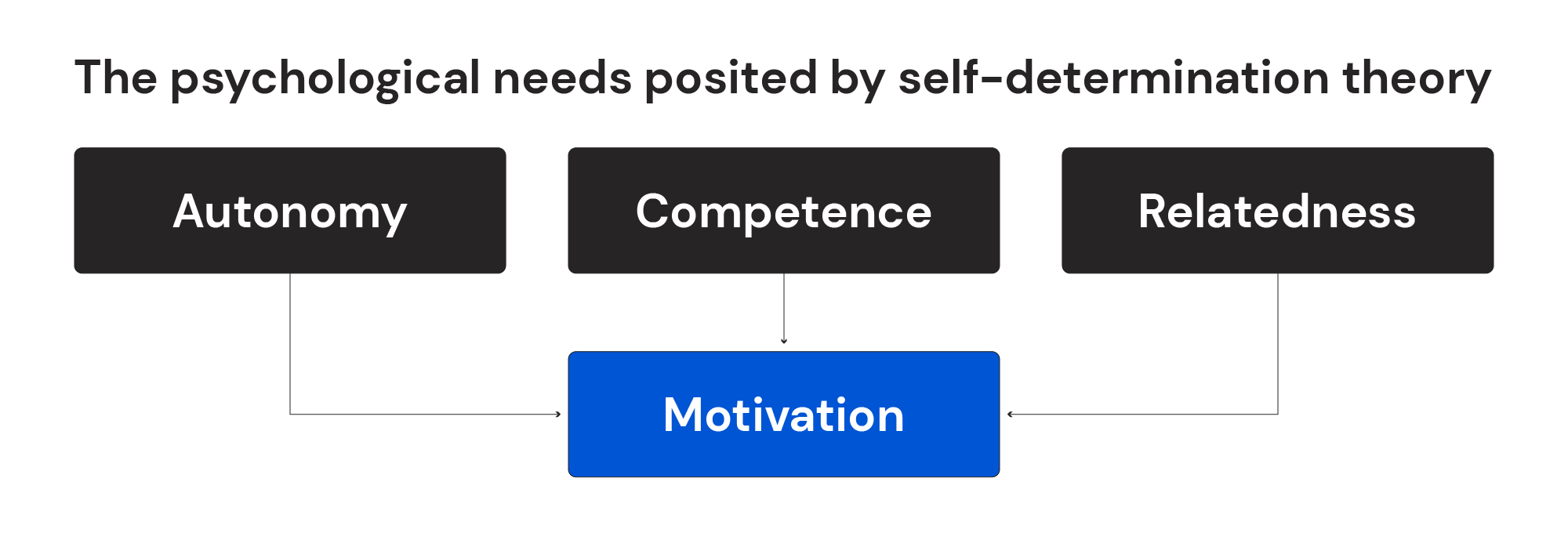

According to the theory, there are three critical psychological needs that facilitate and enable the manifestation of intrinsic motivation and self-determination. Those three needs are competence, autonomy, and relatedness. To give a well-rounded view of each term, I’ll present two proposed definitions for each, according to two different sources (one, two).

Competence refers to “feeling effective in what one does,” or “the need to feel capable of achieving desired outcomes.”

Autonomy refers to “feeling a sense of authentic choice in what one does,” or “the need to feel choiceful and volitional, as the originator of one’s actions.”

Relatedness refers to “being meaningfully connected with others,” or “the need to feel close to and understood by important others.”

These three constructs, and their relationship to motivation, are presented in Figure 5.

When these three psychological needs are met, people tend to feel empowered to confidently and enthusiastically pursue growth opportunities, which are perceived as being very rewarding and fulfilling. When these psychological needs are thwarted, intrinsic motivation will be hard to come by, which threatens long-term success in the goal striving process.

So, after you create the first draft of your goal hierarchy, do a quick audit.

In reference to your goals, do you have satisfactory levels of perceived competence? If not, you might want to add some mastery goals to your hierarchy that involve learning new things or developing new skills that will facilitate a greater sense of competence.

In reference to your goals, do you have satisfactory levels of perceived autonomy? If not, you might want to revise some of the goals in your hierarchy to facilitate a greater sense of competence. For example, if you had a goal that involved doing a 30-day fitness challenge that takes all decisions about exercise and nutrition out of your hands, you might instead shift to a different approach that gives you more control over the trajectory of your fitness journey.

In reference to your goals, do you have satisfactory levels of perceived relatedness? If not, you might want to add some process goals to your hierarchy that include other people. For example, you might join a club that involves regular physical activity, join a recreational sports league, hire a coach with a very collaborative approach, join an online community with similar goals and interests, or team up with a workout partner. You can easily turn these into process goals by codifying your engagement – for example, “work out with a training partner three times per week,” “check in with my coach weekly,” “go hiking with a walking club once per week,” “post twice per week in an online fitness community,” and so on.

Up to this point, we’ve discussed how to set an excellent goal hierarchy, and how to cultivate intrinsic motivation to pursue those goals enthusiastically. However, successful goal achievement typically requires more than a plan and some motivation – we often need to initiate and maintain behavioral changes to make big strides toward our goals.

The COM-B Model of Behavior Change

There’s no question that long-term behavior change is difficult. Take stock of your current day-to-day behaviors. How did they come to be? Are they the same as they were three months ago, or three years ago?

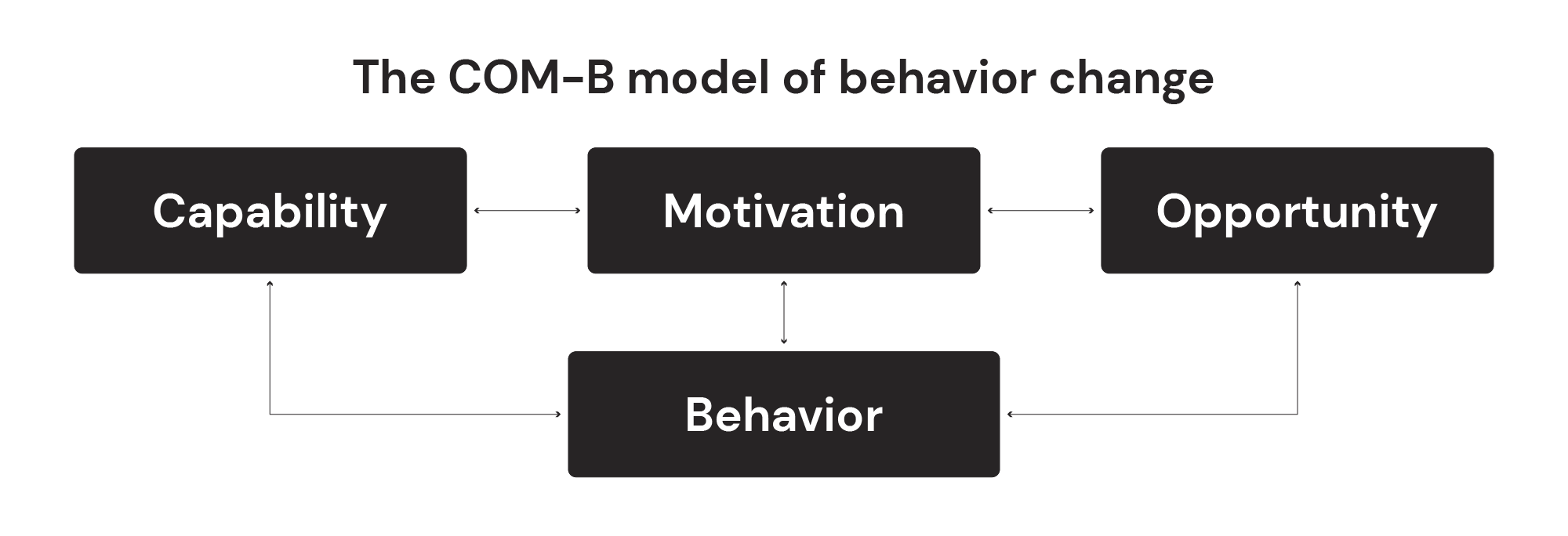

Your behaviors have most likely changed over the years, sometimes quite dramatically. Our values, priorities, and motivations change over time, but there are also many circumstantial and environmental factors that nudge us toward our behavior patterns. Several theories and models have been proposed to describe how humans can successfully change behaviors, but the COM-B model is one of my favorites. It is an acronym proposing that Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation (COM) influence Behavior (B). Motivation is the cornerstone and central factor of this model, with a direct relationship drawn between motivation and behavior. However, the model also acknowledges that both capability and opportunity impact motivation, in addition to directly impacting behavior. This model is summarized in Figure 6.

In order to more deeply understand this model, we need to revisit a previously defined term, and define two others. Earlier in this article, we saw the following definition for motivation:

“The process whereby goal-directed activities are initiated and sustained… In expectancy-value theory, motivation is a function of the expectation of success and perceived value” (source)

If we focus on the bolded words in that definition, we can easily see how capability and opportunity come into play. If the expectation of success impacts motivation, then we need to feel highly capable in order to facilitate motivation for a particular goal, and we need to believe that we have access to all of the opportunities necessary for goal achievement.

That brings us to our new definitions. Capability refers to having the skills, knowledge, psychological capacity, and physical capacity to engage in a given activity. Opportunity refers to “all the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behavior possible or prompt it.” For example, this is where access to resources, a suitable environment, and social support would come into play.

Once again, after you create the first draft of your goal hierarchy, do a quick audit.

Do you feel capable of achieving the goals you’ve laid out? This has considerable overlap with the “competence” component of self-determination theory. For example, when reviewing your goal hierarchy, you might find that some new knowledge or skills are required to simultaneously bolster your sense of competence and capability. In many cases, the actions you take to address competence and capability will be one and the same. However, there are scenarios where you might find a slight divergence between competence and capability.

For example, you might have the core competencies (that is, the knowledge and skills) required to track and modify your dietary intake in accordance with your goals. However, you might have a tendency to snack in a distracted manner, or you might even experience binge eating episodes, which threaten your ability to accurately track intake. In this context, you have the fundamental competencies required for diet tracking, but your perceived sense of capability might be impaired by psychological or attentional factors that lead to dissociated or distracted eating episodes. In order to support this behavior change, one might take steps to limit distracted eating, or seek professional support pertaining to their binge eating episodes.

I can refer to my own training history for another example. About a year ago, I was having issues with training consistency and adherence. It wasn’t an opportunity issue, as I had access to a gym and time blocked off in my daily schedule. It also wasn’t a competence issue – with over a decade of coaching experience, I certainly felt competent with regards to designing a training program for myself. However, I sustained an injury that prevented me from completing a lot of the standard barbell and dumbbell exercises I typically prefer. So, I had the opportunity and competence required to create and execute the plan as it was originally designed, but I had a temporary reduction in physical capability. So, I adjusted the program and some of my goals to be more compatible with my physical capability at the time. Alternatively, rather than adjusting my program and goals based on my capability impairment, I could have potentially sought medical treatment to restore my original level of capability. Whether you resolve a capability shortfall by trying to adjust your goals in accordance with your current capability level or by trying to increase your capability level in accordance with your goals will ultimately depend on the circumstances of the scenario.

Moving on, do you believe you have access to all of the opportunities necessary to achieve the goals you’ve laid out? The examples pertaining to this facet of the COM-B model are virtually limitless, as “opportunities” refer to “all the external factors that lie outside an individual that make behavior possible or prompt it, including physical and social factors.” This could involve building a suitable social environment that is supportive of your goal striving process. It could also involve restructuring your schedule or physical environment to reduce the friction that exists between you and the behaviors you wish to implement, or to increase the friction that exists between you and the behaviors you wish to cease. This is also where tools and resources come into play.

Continuing the example about food tracking, you might have all of the knowledge and skills necessary to track your food intake, but you might find that tracking by hand is so tedious that you’re unable to do it consistently. This is a prime example of where apps with convenient and efficient food logging functionality can have a meaningful impact on behavior change. I would personally recommend MacroFactor for this purpose – my bias is obvious, but it’s also a quantifiably excellent app in terms of ease, efficiency, and speed of food logging workflows.

Shifting back to my example about training around an injury, we can adopt a totally different perspective that leads to a different solution. As you’ll recall, I was unable to complete my training program as written due to an injury-induced change in capability. So, I adjusted my training program and some of my training-related goals. However, I could have theoretically framed this as a lack of opportunity – it’s possible that I could have kept making satisfactory progress toward my original goals, if only my gym had more specialized equipment to help me train around the injury. So, rather than viewing my injury as a capability issue to be resolved by adjusting my program and goals, I could view it as an opportunity issue to be resolved by seeking a gym with more suitable equipment.

Now, let’s fast forward to the future, when my injury will be a distant memory. It’s quite possible that I’ll be back to my preferred barbell and dumbbell exercises, but I’ll still be hauling myself all the way across town for each workout. It’s not hard to imagine a scenario where the longer commute becomes one of my largest obstacles or sources of friction related to my fitness goals. In such a scenario, I might make the exact opposite change, switching back to a gym that is less equipped with specialized machines but more geographically convenient. Circumstances will inevitably change over time, so we have to continuously assess (and reassess) our capabilities and opportunities as we pursue our goals.

In summary, we set the stage for behavior change by establishing a well-designed goal hierarchy and ensuring that we’re fulfilling the psychological needs that allow intrinsic motivation to manifest. However, the next step is to put the COM-B model to work by assessing our capabilities and opportunities pertaining to the goals in our hierarchy. If there is a scenario in which we have insufficient capabilities or opportunities for a specific goal, we have two options: seek out the necessary capabilities or opportunities, or adjust the goal hierarchy to reflect the capabilities or opportunities that we have access to.

An Integrated Model of Motivation and Behavior

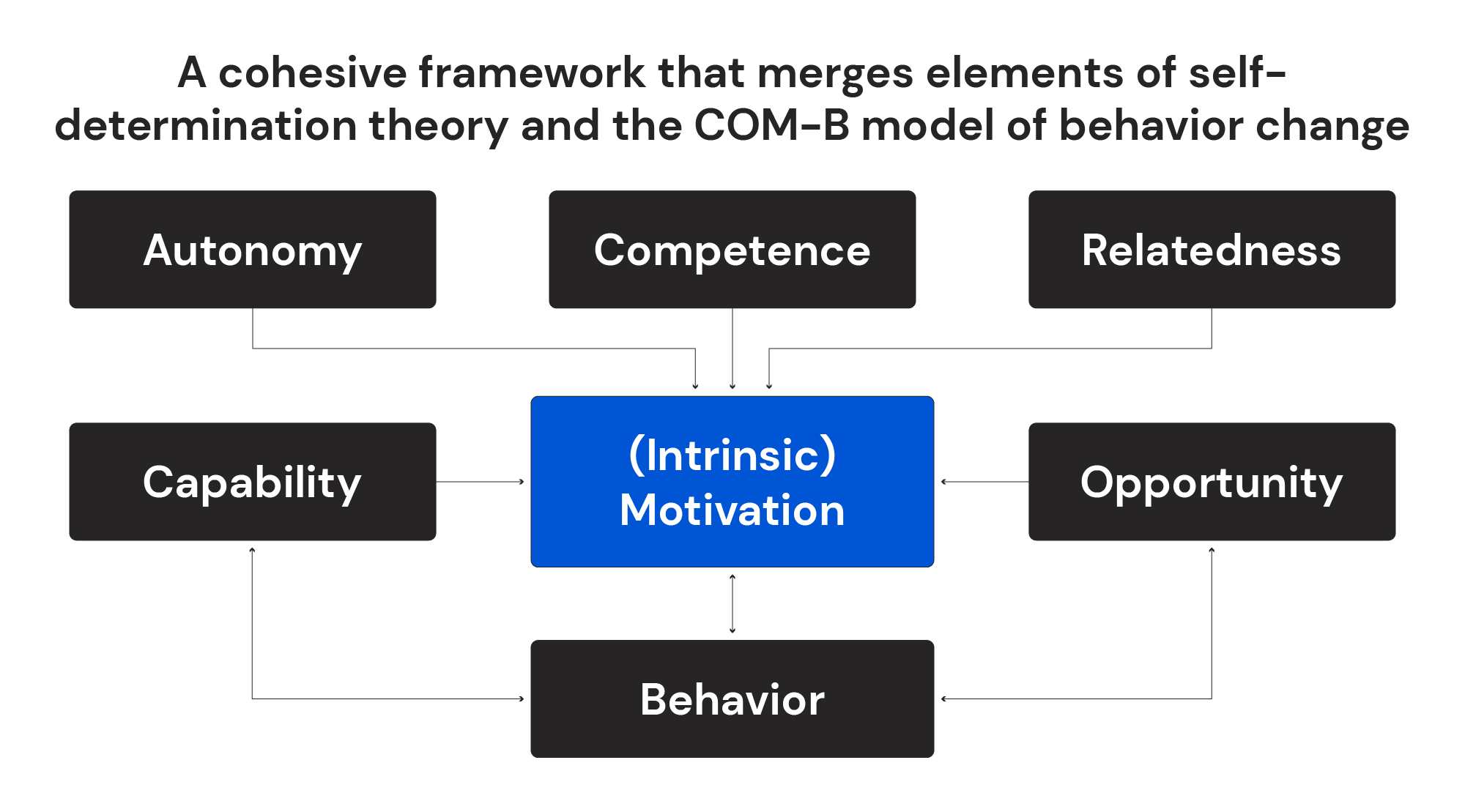

At this point, we’ve discussed goal hierarchies, self-determination theory, and the COM-B model of behavior change. While it might seem like three disconnected concepts or theories on the surface, that couldn’t be further from the truth. In reality, all three can be combined into a cohesive and comprehensive model of motivation and behavior.

The goal setting process sets the stage for motivation – after all, most definitions of “motivation” specifically frame it in reference to a particular goal (or set of goals). We establish a goal hierarchy so we can identify what we’re getting motivated for. After that, we need to facilitate the conditions that allow intrinsic motivation to manifest. This involves taking stock of our key psychological needs (competence, relatedness, and autonomy), and bolstering any psychological needs that appear to be lacking.

Willmott et al state that: “According to the COM-B model, for a given behavior to occur, at a given moment, one must have the capability and opportunity to engage in the behavior, and the strength of motivation to engage in the behavior must be greater than for any other competing behavior.” A well-designed goal hierarchy identifies key behaviors that ought to be changed, self-determination theory enables us to foster high levels of intrinsic motivation to change those behaviors, and the COM-B model helps us identify important barriers to the behavior change process.

So, once we have a well-designed goal hierarchy and a great deal of intrinsic motivation to pursue those goals, the final thing we need to do is change behaviors related to the items in our goal hierarchy. To support persistent behavior change, we need to take stock of our capabilities and opportunities pertaining to the items in our goal hierarchy. If we notice any insufficiencies, we need to either find strategies or resources to enhance our capabilities and opportunities, or we need to modify the goal hierarchy to be more compatible with the capabilities and opportunities available to us. This cohesive framework combining self-determination theory and the COM-B model of behavior change is presented in Figure 7.

How to Apply This Conceptual Model

When beginning to pursue a new goal

When you’re first starting to pursue a brand new goal, this conceptual model gets applied in a “forward” direction. You begin by establishing a solid, well-aligned goal hierarchy. Then, you take stock of the key psychological needs associated with self-determination theory: competence, autonomy, and relatedness. If you notice that one or more of these psychological needs requires some proactive support, you can put a plan in place to bolster that need before the goal pursuit process even begins. Finally, now that we’ve leveraged self-determination theory to cultivate a high level of intrinsic motivation to accomplish the goals within our goal hierarchy, we can focus on the two other components of the COM-B model: capability and opportunity. Think through these two components, and make some proactive modifications if necessary. For example, if you have concerns about capability, you might consider incorporating a goal into your hierarchy that involves learning a new skill that will enhance your perceived capability level. If you have concerns about opportunity, you might consider acquiring some tools, resources, or social support systems to help you out along the way. By considering this conceptual model that combines self-determination theory and the COM-B model, you can set yourself up for success by setting effective goals and addressing the key factors that support sustainable motivation and behavior modifications.

When you run into some friction or challenges while pursuing a goal

There’s no question that a great goal hierarchy, combined with proactive consideration of self-determination theory and the COM-B model, can set you up for a great start to your goal striving process. However, even with the greatest of starts, it’s very likely that you’ll eventually run into some friction or challenges while pursuing your goal. Many goals take months, if not years, to achieve. Seasons change, we move from one apartment to another, we change jobs, and so on. Throughout long stretches of time, we run into a variety of factors that can impact our environment, schedule, mindset, priorities, social support, and more. As a result, we might find that motivation starts to wane, or that it is increasingly difficult to engage in behaviors or meet goals that previously felt quite easy.

When this occurs, I like to “run the model in reverse.” Instead of starting at the beginning (goal setting), I start at the end (the COM-B model). I begin by considering whether or not my current challenges might be driven by shortcomings related to capability or opportunity. If so, I address that shortcoming and get right back to goal striving. If I don’t see any issues related to capability or opportunity, I shift my sights toward motivation (and, by extension, self-determination theory). At that point, I consider whether or not my current challenges might be driven by shortcomings related to my key psychological needs (competence, autonomy, and relatedness). If so, once again, I address that shortcoming and get right back to goal striving. If I don’t see any issues related to competence, autonomy, and relatedness, then the situation is slightly more complicated.

In such a scenario, I’ve confirmed that I have the capabilities and opportunities needed to support behavior change. I’ve also confirmed that I’m meeting the key psychological needs necessary to support the intrinsic motivation required to pursue my goals. At that point, the issue might be the goals themselves.

When the COM-B model and self-determination theory don’t point me toward a clear solution, I take a moment to seriously consider whether or not I’m pursuing the right goals. The reality is that our goals, priorities, and “idealized sense of self” can change over time. There’s nothing wrong with that – in fact, it can sometimes be a sign of personal growth. This means that you can construct a fantastic, well-aligned goal hierarchy when you get started, but this goal hierarchy can become less and less suitable for you over time. In this situation, the best path forward is to revisit the goal hierarchy and redesign it to reflect your current values, priorities, and ambitions. Changing your goals should not be viewed as “failing” or “giving up” – you’re simply recalibrating your goal hierarchy, which is necessary from time to time. Once it is recalibrated, you’ll be right back on your path to pursuing goals that are enriching, fulfilling, and meaningful to you.

Can an “Adherence-Neutral” App Really Support Behavior Change?

Defining “Adherence-Neutral”

Since launching MacroFactor, one topic that’s received a lot of attention is the adherence-neutral approach of our algorithm and design elements. For many, it’s been a breath of fresh air among diet apps with unrealistic and counterproductive constraints related to adherence. We have, however, come across some questions related to this concept. For example, how can someone achieve their goals if they don’t adhere to their dietary targets? How can a diet app promote behavior change without a system of rewards and punishments tied to adherence? These are great questions, but they’re ultimately rooted in some misconceptions. So, before we get too deep into the motivation and behavior change research, let’s take a brief moment to clear up these misconceptions and clarify the science behind MacroFactor’s adherence-neutral approach to behavior change and goal attainment.

Imagine you’re getting in your car and driving to a destination you haven’t visited in many years. Naturally, you might use a navigation app to lead the way. So, you put your starting address and your intended destination into an app. Can you imagine if the app gave you a set of directions from a generic location in your general region, rather than your actual starting address? And what if the app didn’t give you an estimated time of arrival, or even provide live, turn-by-turn directions as you drove? This functionality would be less useful than an old fashioned map, which would at least enable you to trace the path from your true starting location. Believe it or not, this is how a huge number of diet apps work. They make general estimates about your initial calorie needs (which might be kind of close to your actual starting point), give you a calorie target, and never really update from there.

Now, back to our driving metaphor. That first app wasn’t very useful, so you upgrade to a navigation app that will actually provide live, step-by-step directions as you go. However, it’s busy out there, you couldn’t quite get over to the correct lane in time, and you missed a turn. You were already a little doubtful about remembering the correct route to your destination, but now that you’ve made a wrong turn in unfamiliar territory, you need the navigation app more than ever.

We all know what happens next. The font turns red, and a punitive message pops up: “You missed your turn! Not missing turns is an important part of successful navigation, so make sure you don’t miss turns anymore.” Then the app reminds you what the route should have been, and lets you try again tomorrow or next week.

Obviously no navigation app would actually operate this way, but that’s a fairly accurate representation of how many diet apps work. When you make a wrong turn, any decent navigation app will determine exactly how far you’ve strayed from the original course, then provide updated guidance for your next steps and adjust your anticipated time of arrival. It is, quite literally, the only justifiable way for a navigation app to respond, and we feel the same way about diet apps.

Now, why do I bring this up in an article about motivation and behavior change?

First, some people have misinterpreted the “adherence neutral” concept. At the simplest level, some people assume that the app promises to deliver your selected goal, regardless of how you eat. In other words, they assume that the app is making a completely implausible claim about delivering successful body composition outcomes without any need to modify diet or exercise behaviors. Clearly, this is not the case.

“Adherence neutral” does not mean that your results are totally disconnected from your adherence to your diet targets. Your diet and physical activity habits impact changes in weight and body composition, and there’s no getting around that. “Adherence neutral” means the app’s algorithmic functions will continue working without a hitch, even when adherence slips. A GPS unit doesn’t shut down when you make a wrong turn or hit traffic; it calculates a new route or changes your estimated arrival time accordingly. Our algorithm doesn’t create an arbitrary threshold for “sufficient” or “insufficient” adherence, nor does it fail to update weekly targets when you go above or below your nutrition targets. The app simply analyzes what you did, how your body responded, and updates the route to your goal and your estimated arrival time.

Second, some people erroneously worry that an adherence-neutral app will fail to motivate them or reinforce behavior change. They want an app that requires them to be perfectly adherent, and punishes them when they deviate (even slightly) from their nutrition targets. In most cases, those punishments take the form of discouraging design elements (changes in font colors, notifications, or banners) and decreased app functionality. For example, some apps may simply not work well if you deviate from targets (they might have static nutrition targets that never change in response to your logged dietary intakes). Even for dynamic apps that claim to have “nutrition coaching” functionality, some may refuse to update your nutrition targets if your adherence falls below a certain threshold, and just repeat the same targets (and essentially ignore all of your tracked nutrition data) until you “get your act together.” Can you imagine hiring a nutrition coach that ignores all your emails when you start having challenges? It’s hard to justify hiring a coach who hangs around to enjoy the good times, then disappears when the going gets tough – the entire purpose of a diet coach is to provide support when you need it the most.

Why an adherence-neutral approach is the best way to support motivation and behavior change

Now that we’ve explored motivation and behavior change in an evidence-based manner, we can see why an adherence-neutral app is actually better, not worse, for supporting motivation and behavior change.

When an app dichotomizes adherence (good or bad; sufficient or insufficient), it is explicitly reinforcing rigid cognitive restraint. Compared to flexible restraint, the scientific evidence strongly indicates that rigid restraint is associated with a lower likelihood of goal achievement and a higher likelihood of psychological distress during the goal striving process.

When you’re prioritizing adherence just to avoid in-app punishments, you’re experiencing a very low-quality form of motivation, which is totally extrinsic in nature. This might work for two weeks or two months, but not for two years.

When you do experience in-app punishments, they crush intrinsic motivation by detracting from your sense of competence and capability. As discussed in a prior article, the combination of rigid restraint and deviation from nutrition targets can lead to motivational collapse, and punitive in-app responses only increase that likelihood.

When an app provides static nutrition targets that never change in response to your progress, or fails to update targets when your adherence drops below an arbitrary threshold, it threatens your sense of autonomy and relatedness. You’re isolated with no individualized support, and you’re stuck with the targets you’ve been given.

In contrast (here’s the sales pitch part), consider MacroFactor. It was specifically built with flexible cognitive restraint in mind. It has ample flexibility, with different modes of operation (coached, collaborative, and manual), and even the coached option provides plenty of flexibility for selecting your preferred style of diet, protein intake level, and rate of weight change. As a result, you can choose the level of autonomy you prefer. There are no punitive design elements or changes in functionality to thwart your sense of competence or capability when adherence slips. MacroFactor continues giving updated and individualized support, both when things are going smoothly and when things are getting tough. If that’s not enough to support your sense of relatedness, we have fantastic communities on Reddit and Facebook to take your social support to the next level.

In summary, some diet apps have completely static nutrition targets that never change. Aside from necessarily forcing you into adherence (or failing to work entirely), these apps lack the level of individualized target optimization necessary to support successful goal striving for a large percentage of users. Some diet apps update nutrition targets, but only when your adherence level is deemed “acceptable.” This is sometimes framed as a mechanism to support motivation and behavior change, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. This approach of forced adherence and in-app punishment is completely out of step with the scientific evidence pertaining to motivation and behavior change. An adherence-neutral app isn’t merely able to support motivation and behavior change – it’s the best way to support motivation and behavior change, according to the science.

Conclusions

It can be challenging to set effective goals, but evidence-based goal setting is only the first step. Once you’ve established a comprehensive and well-aligned goal hierarchy, you need to cultivate and sustain motivation to pursue those goals, and implement the persistent behavioral changes necessary to achieve them. Fortunately, you don’t need to manufacture motivation out of thin air – by bolstering the key psychological needs associated with self-determination theory (competence, autonomy, and relatedness), you create the conditions that allow intrinsic motivation to manifest. In addition, you don’t need a huge list of tips and tricks to make behavior change a reality. Once motivation is effectively supported, you only need to bolster the key components of the COM-B model of behavior change (capability and opportunity). By sequentially leveraging the concepts of goal hierarchies, self-determination theory, and the COM-B model of behavior change, you have a start-to-finish process to set yourself up for success. When you run into challenges during the goal striving process, all you need to do is work backwards until you identify and resolve the issue that is causing the friction. So, by combining these three concepts, you get a blueprint for success that helps you begin your goal striving journey on the right foot, and helps you troubleshoot challenges as you go.