If you consume a lot of fitness content, you’ve probably heard of refeeds and diet breaks. Some people suggest that these strategies are complete game changers for dieters with fat loss goals, while others say they’re useless. So, let’s dive into the research to see if refeeds and diet breaks are worth pursuing.

What Are Refeeds and Diet Breaks?

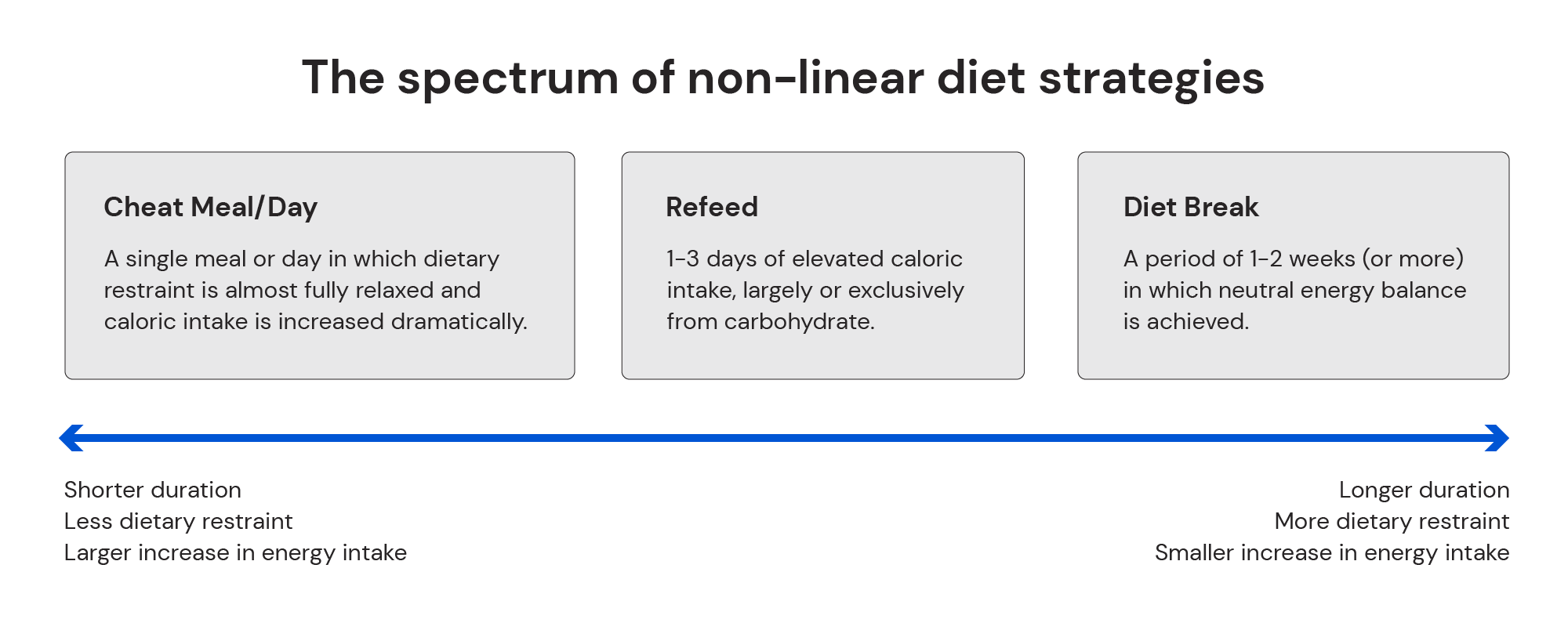

Refeeds and diet breaks fall on a spectrum of what we might call “non-linear dieting strategies.” That’s probably a misnomer – whether we’re talking about longitudinal trends in body weight or daily calorie intake, dieting is virtually never a linear process, even when approached with the most linear of intentions. Nonetheless, non-linear dieting strategies involve variation in calorie intake, resulting in certain days or weeks that involve higher or lower calorie intake.

The simplest example would be the choice to include a weekly “cheat day.” As discussed in a previous MacroFactor article, this generally isn’t the most advisable option. However, the concept is simple: there are days where you aim for your typical calorie target, and certain designated cheat days where your caloric intake will be considerably higher.

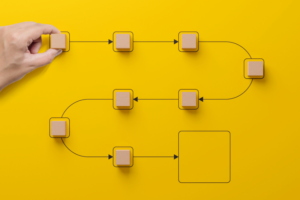

Refeeds are like a more strategic and structured alternative to cheat meals. Instead of choosing one day to let loose and eat in a fairly unstructured or unrestricted manner, refeeds are designated days in which calorie intake is intentionally increased by a specific, predetermined amount, with most (or all) of the extra calories coming from carbohydrates. Some people do one weekly refeed, while others may opt for 2-3 refeeds per week. In many cases, people will bump their calories all the way up to their maintenance level on refeed days (that is, their caloric deficit shrinks all the way to zero). As a result, someone who decides to start incorporating refeeds will often reduce their caloric intake on non-refeed days to maintain their normal weekly calorie deficit. For example, Figure 1 shows a study protocol from a fairly recent study on refeeds. The “standard” diet involved a daily calorie deficit of 25%, while the refeed group had a 35% deficit on normal days and no deficit on their two weekly refeeds.

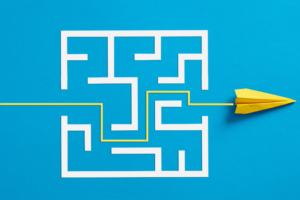

Diet breaks occur over a very different timeline when compared to cheat meals, cheat days, or refeeds. A diet break typically involves shifting from a caloric deficit (negative energy balance) to maintenance calorie intake (neutral energy balance) for at least a week. Sometimes dieters will get sick of dieting and opt for a fairly long-term diet break lasting 1-2 months (or longer). In other cases, dieters will use diet breaks as part of a cyclical plan that involves repeatedly alternating between 1-3 weeks of dieting (negative energy balance) and 1-2 week diet breaks (neutral energy balance). For example, Figure 2 shows a study protocol from a recent diet break study that I co-authored with a fantastic team of researchers. The “standard” approach involved six consecutive weeks of dieting, while the diet break group alternated between cycles of two weeks of dieting and one-week diet breaks.

So, in summary, non-linear dieting strategies fall on a bit of a spectrum. This spectrum is depicted in Figure 3, which is modified from one of my previously published research papers. Diet breaks tend to involve longer durations, more dietary restraint, and smaller increases in caloric intake, whereas cheat meals or cheat days tend to involve very short durations, minimal dietary restraint, and have the potential to yield very large increases in caloric intake. In most common applications, refeeds fall somewhere in the middle.

Why Do People Use Refeeds and Diet Breaks?

We’ve established what refeeds and diet breaks are (and what they typically look like), but we haven’t addressed an important question: why bother?

For some people, it’s as simple as increasing dietary flexibility for specific periods of time (such as a social event or vacation), or opening up specific parts of the week where it’s more feasible to work some indulgent, hedonically pleasing food options into one’s diet. This is typically how people use cheat meals (or, the more advisable alternative known as planned hedonic deviations), but a refeed can functionally serve the same purpose. For a more in-depth discussion about the pros and cons of using this type of strategy to increase dietary flexibility or implement higher-calorie days for the sake of hedonic enjoyment, be sure to check out our previous article about cheat meals.

In other applications, refeeds are often viewed through a more strategic, performance-oriented lens. High-intensity exercise performance can be impaired by a combination of calorie restriction and excessive carbohydrate restriction, so avid exercisers sometimes like to shift more carbs around their most important workouts while dieting. For example, a bodybuilder might notice that their lower body is lagging behind their upper body, and that their lower body workouts tend to be particularly draining. When dieting, they might shift more calories to the day before (or the day of) their leg workouts, in hopes of increasing their energy and performance in the gym. Diet breaks can also be used in a similar manner if there’s a week or two of training that is particularly arduous or important – during this time window, extra calories might be viewed as a helpful tool to support performance or recovery.

Having said that, the most frequently discussed application of refeeds and diet breaks relates to the concept of metabolic adaptation. This article describes just about everything you’d ever want to know about metabolic adaptation, but the overall concept can be described pretty concisely. If you’ve ever attempted a weight loss diet, you might have noticed that it eventually got a bit harder over time. At first, you were dropping weight steadily at a caloric intake of 2200 Calories per day, but now you’ve plateaued without making any changes to your exercise or diet. Why is that?

One factor driving your plateau is the fact that you used to have a larger body, and now you have a smaller body. A smaller body burns fewer calories at rest, and requires fewer calories when moving around throughout the day. However, there’s a second factor at play: as your body senses that energy reserves are running low, it tries to become a bit more efficient with how it uses energy. Our species evolved long before grocery stores started popping up, so it’s easy to see why it’d be advantageous to develop the ability to reduce energy expenditure during periods of famine.

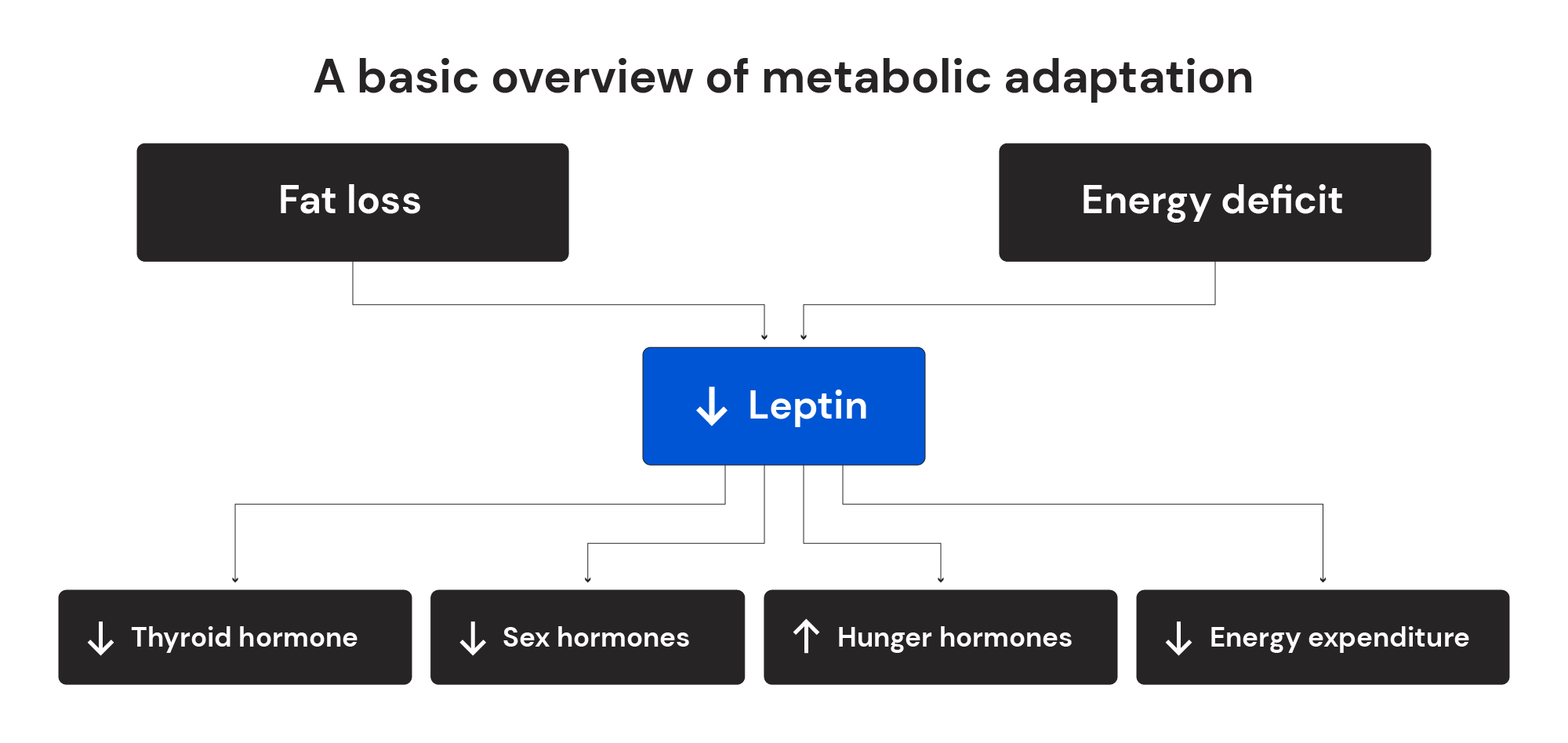

If we reduce calorie intake or lose fat mass (or if we do both, as in the case of dieting), we experience reductions in blood levels of a hormone called leptin. When the brain (and more specifically, the hypothalamus) notices this drop, the body responds with some adaptive responses that reduce energy expenditure. To use an analogy, it’d be like driving a car that can progressively increase its fuel efficiency as the gas tank gets emptier and emptier. When gasoline is getting low, a car might try to reduce the impact of nonessential features that use up energy (such as the air conditioner or heater) and turn on a light to encourage you to go fill up. Similarly, the body reduces the energy cost of certain biological processes, minimizes wasteful activities (like fidgeting or unnecessary movement), and increases hunger. This is represented in Figure 4.

That paints a pretty bleak picture of metabolic adaptation, and makes it seem like we are doomed to fail when dieting. Fortunately, that’s not the case. As discussed in a previous article about reverse dieting, metabolic adaptation doesn’t seem to be a major predictor of the ability to lose weight or maintain weight loss over time. Nonetheless, dieters would love to minimize friction as much as possible, so there is considerable interest in finding strategies to reduce the impact of metabolic adaptation.

That’s where refeeds and diet breaks come into play. As shown in Figure 4, metabolic adaptation is driven by two primary factors: the loss of fat, and the presence of a caloric deficit. There’s not much we can do about fat loss – if we try to reduce fat loss to minimize metabolic adaptation, but we are trying to minimize metabolic adaptation to facilitate fat loss, then we aren’t doing ourselves any favors. In contrast, we might theoretically be able to manipulate the caloric deficit in order to influence leptin levels.

Research indicates that leptin drops fairly quickly when we begin to restrict energy intake, and the drop is particularly large when we restrict carbohydrate intake. However, leptin levels increase relatively quickly when energy intake (and carbohydrate intake) are restored.

This has led people to wonder if we can reverse, attenuate, or fully mitigate metabolic adaptation by periodically boosting leptin levels using non-linear dieting strategies. For example, what if we had 2-3 days throughout the week where carbohydrate intake increases and the energy deficit is eliminated (i.e., refeeds)? What if we had 1-2 weeks every month or two where the energy deficit is eliminated (i.e., diet breaks)? When I first started publishing research about metabolic adaptation back in 2014, I felt these were totally legitimate questions, and we didn’t yet have research to validate or invalidate these proposed strategies. Fortunately, in the years since, researchers have conducted a handful of studies that put them to the test.

Do Refeeds Work?

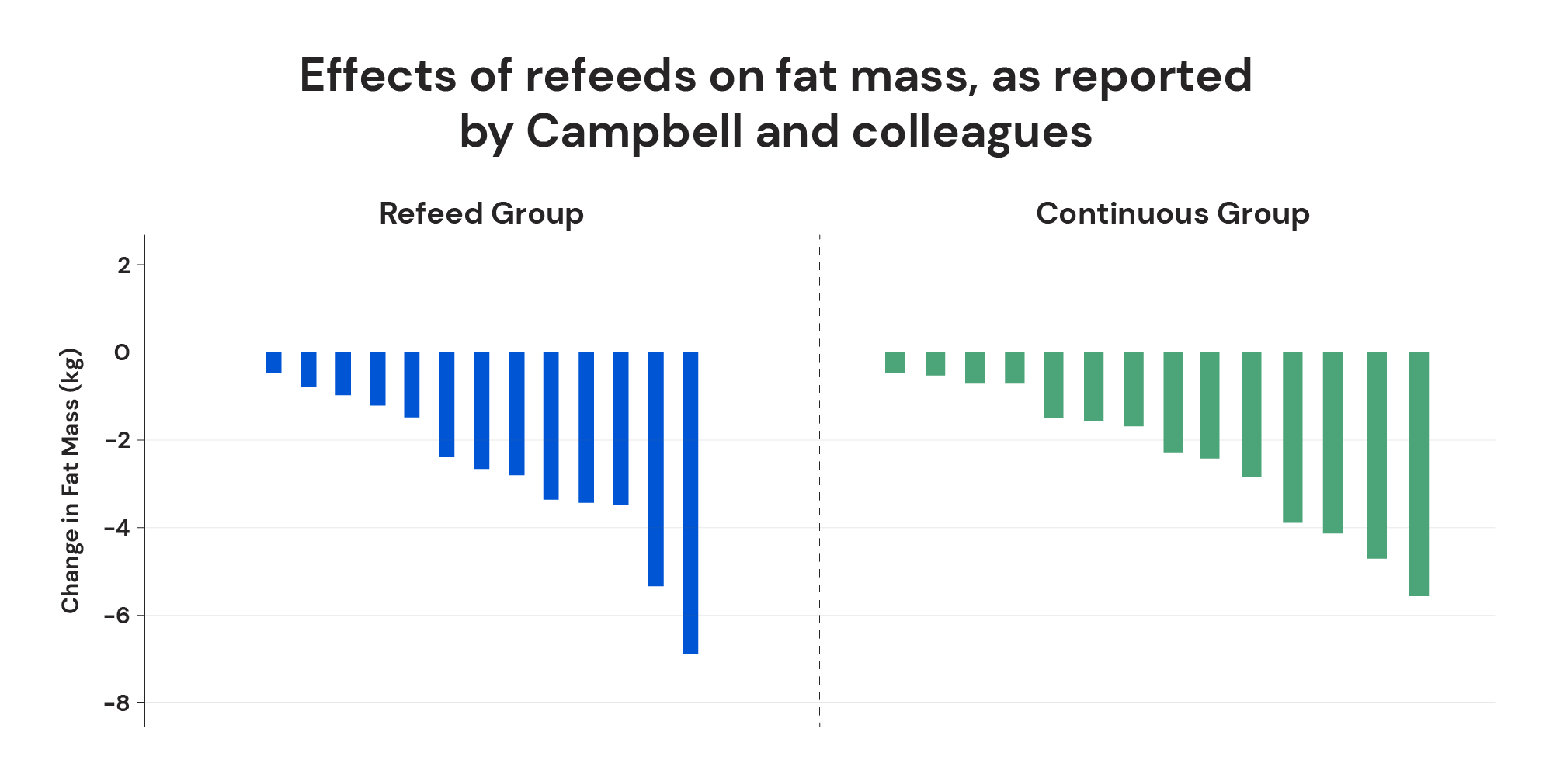

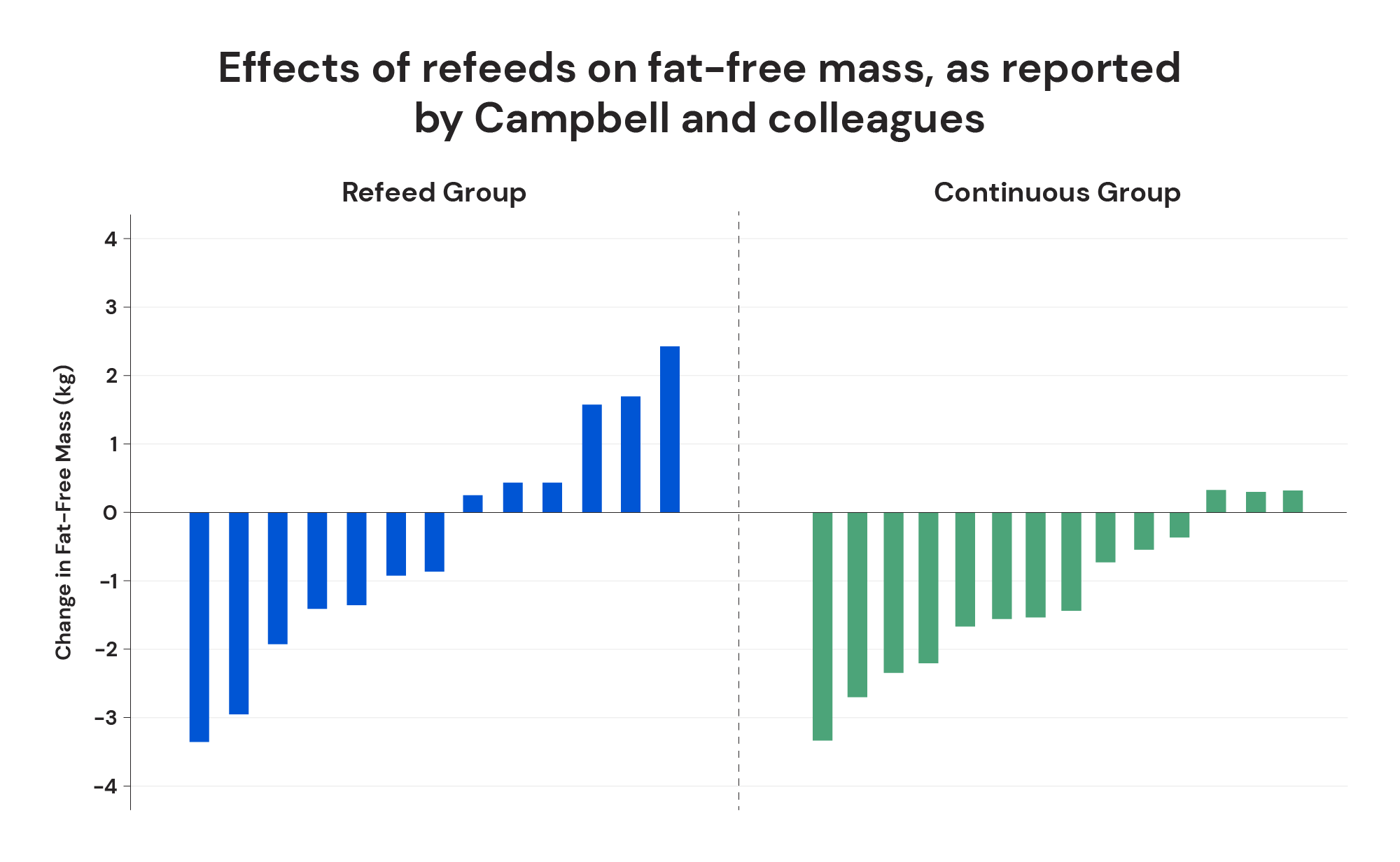

The most direct refeed research comes from the laboratory Dr. Bill Campbell, who (in the interest of transparency) happens to be a friend and collaborator of mine. In their 2020 study, they used the diet protocol that was previously presented in Figure 1; the control group dieted with a 25% calorie deficit, while the refeed group spent five days per week in a 35% deficit, and two days per week in neutral energy balance (0% energy deficit). The study was completed by 27 healthy, physically active individuals (14 men and 13 women) who completed a resistance training program throughout the study

The effects on fat mass are presented in Figure 5. In short, the individuals in both groups experienced very similar reductions in fat mass. The effects on fat-free mass are presented in Figure 6. There were a few folks in the refeed group who experienced particularly good gains in fat-free mass, but the statistical analysis did not indicate that the refeed group experienced significantly better gains on average. Similarly, neither group experienced a significant advantage when it comes to changes in resting metabolic rate, which was the only energy expenditure outcome measured.

On the surface, it seems like this study conclusively shows that refeeds “don’t work,” if the intended purpose is to maintain higher energy expenditure or lose more fat mass. However, there are a few important caveats to keep in mind. With only 13-14 participants per group, we shouldn’t necessarily assume that this study perfectly captures the typical effect for all of humanity. In addition, the researchers were only able to measure resting metabolic rate (rather than total daily energy expenditure), which is a common limitation in this type of research. Most notably, participants only lost a few kilograms on average, and resting metabolic rate only dropped by around 50-60 Calories per day. In other words, it’s unlikely that substantial metabolic adaptation occurred, given that the weight loss intervention was pretty modest in magnitude. As a result, we shouldn’t expect a massive impact of any intervention that aims to partially attenuate metabolic adaptation. To lean on a metaphor, imagine a hypothetical study investigating a new pain relief medication. If it’s tested in a group of people experiencing very little pain, the medication won’t have an opportunity to reveal its true impact.

Nonetheless, I am increasingly convinced that the metabolic impact of refeeds is pretty negligible in the context of metabolic adaptation. In studies looking at leptin responses to transient shifts in energy intake, cumulative energy balance seems to be the most important determinant of leptin levels. In other words, leptin levels are primarily driven by how many calories you ate across the entire week or month, rather than being meaningfully altered by shifting some calories from Tuesday to Wednesday.

In addition, there’s a considerable amount of research on intermittent fasting strategies, which could arguably be viewed as a fairly extreme approach to refeeding. In these protocols, people might fast entirely (or consume only a few hundred Calories per day) for 2-3 days per week, without substantially dropping their calories on the other days of the week. In this context, we can argue that the individual is basically using 4-5 refeeds per week, while still establishing a caloric deficit across the entire week of eating. Research suggests that this is a viable approach to fat loss, but doesn’t necessarily appear to be more or less effective than a more standard weight loss approach that involves a stable daily energy deficit (one, two, three).

So, for the vast majority of dieters, it doesn’t appear that refeeds confer any physiological advantages that meaningfully attenuate metabolic adaptation or increase fat loss. We can’t rule out the possibility that refeeds are helpful in fairly extreme weight loss scenarios that haven’t been studied as extensively (such as very large magnitudes of weight loss, or dieters pushing to extremely low body-fat levels), but I still wouldn’t expect a huge impact in these situations.

Do Diet Breaks Work?

Refeeds might not be the antidote to metabolic adaptation, but what if our body simply needs a longer break from the energy deficit?

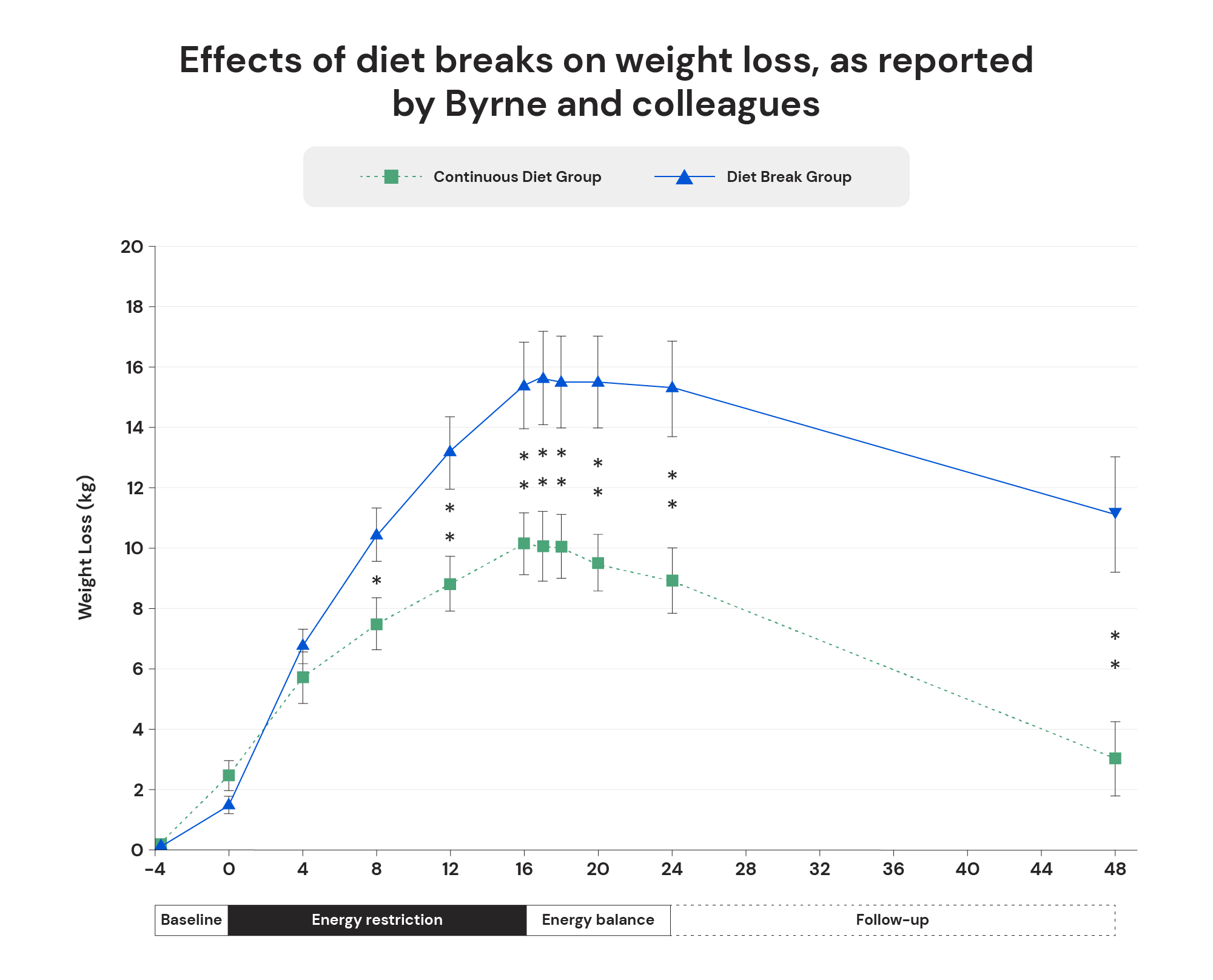

A 2018 study by Byrne and colleagues certainly appears, on the surface, to lend support to this idea. In the study, 51 men with obesity were assigned to a standard 16-week weight loss intervention or an intervention with diet breaks. Participants in the diet break group alternated between two weeks of dieting and two-week diet breaks (at neutral energy balance), resulting in a total intervention length of 30 weeks (with 16 of those weeks spent in an energy deficit).

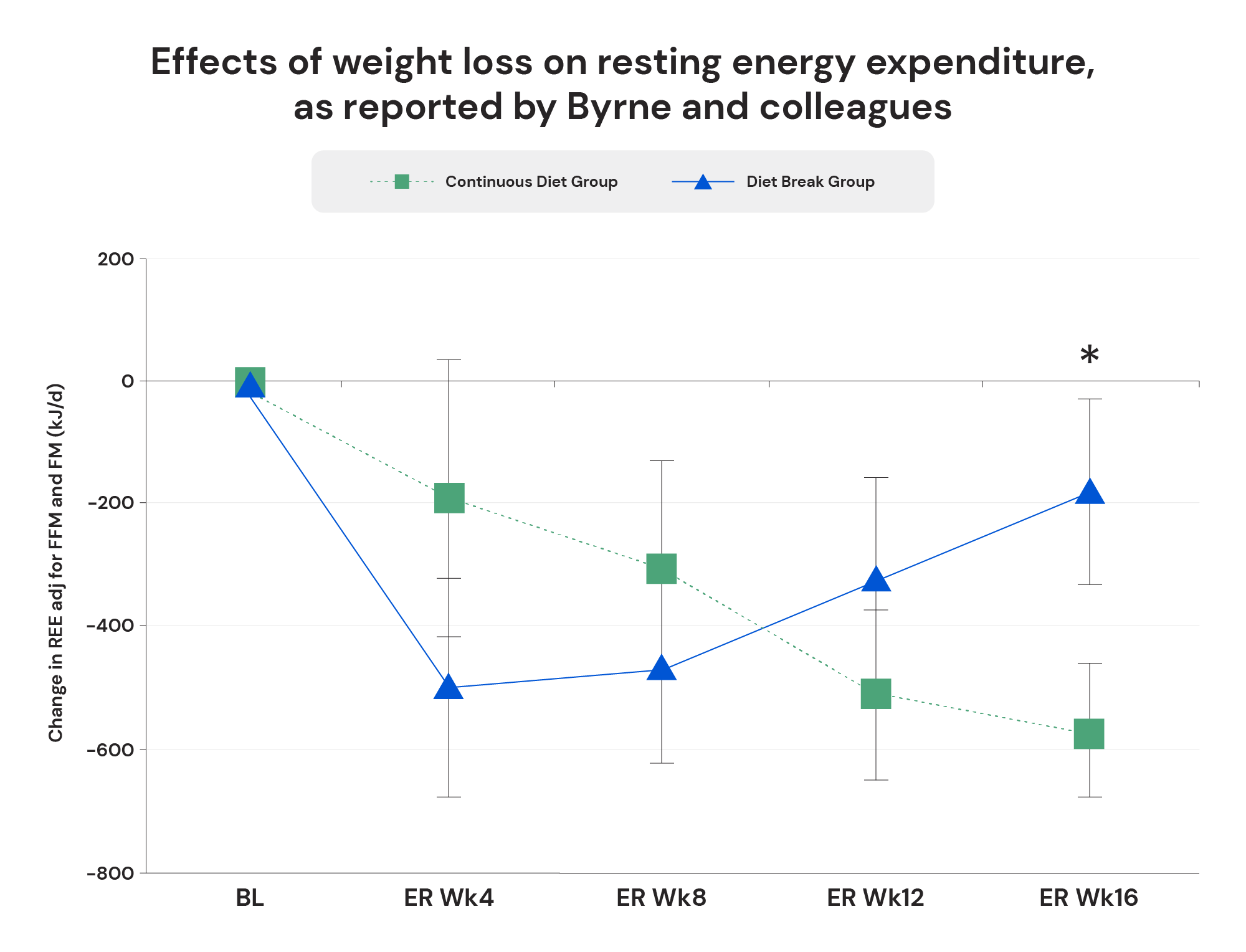

As shown in Figure 7, the folks using diet breaks lost substantially more weight, and the advantage seemed to persist for months after the weight loss period was over. The researchers also noted that, after correcting for changes in body composition, the diet break group appeared to experience smaller reductions in resting energy expenditure by the end of the weight loss period.

This might look like a straightforward confirmation that diet breaks enhance fat loss by attenuating metabolic adaptation, but it’s not quite that simple. First, the differences in resting energy expenditure are not nearly big enough to explain the large differences in weight loss when comparing the diet break group to the control group. It’s possible that unmeasured changes in non-exercise activity thermogenesis made a contribution above and beyond the observed effect on resting energy expenditure, but the large differences in weight loss suggest that some other factors (such as improved hunger management or psychological advantages favoring better dietary adherence) played a major role. For example, it’s quite possible that many people are better able to focus on short “bursts” of weight loss effort, as long as they have regular opportunities to take their foot off of the gas pedal and relax their diet a little bit. In addition, the data in Figure 8 follow a pattern that is hard to explain – why would resting energy expenditure drop more rapidly in the diet break group, then follow a totally different trajectory and recover over time? It’s likely that the adjustments for body composition changes led to these divergent trajectories. If we check the unadjusted values, we see that the raw, absolute drops in resting energy expenditure were not significantly different when comparing the two groups.

Since the 2018 paper by Byrne and colleagues, two additional diet break studies have been published. In 2021, Peos and colleagues published a paper showing no significant benefits for weight loss, fat loss, or resting metabolic rate when comparing a diet break strategy (cycling between three weeks of dieting and one-week diet breaks) to a standard weight loss diet. Nonetheless, the diet break group reported more favorable changes in outcomes related to hunger, appetite, and desire to eat. Within the past couple of months, my colleagues and I also published a diet break paper, in which the diet break group alternated between two weeks of dieting and one-week diet breaks. The study, spearheaded by Madelin Siedler and Dr. Bill Campbell, found no significant advantage of diet breaks for weight loss, fat loss, or resting metabolic rate when compared to a standard weight loss diet. However, diet breaks were slightly better for reducing dietary disinhibition, which is “a behavioral indicator of a loss of control over eating, where an individual consumes greater quantities of food, independently of their level of restraint.”

If you were a very adamant proponent of diet breaks, you might argue that the results of the Byrne study show that diet breaks enhance fat loss, reduce drops in resting energy expenditure, and probably reduced drops in non-resting energy expenditure, which wasn’t directly measured. You might also argue that Peos et al and Siedler et al failed to identify significant weight loss advantages because the total amount of weight lost in those studies was much lower, which makes it far less likely that metabolic adaptation would occur in the first place – it’s hard to show that something attenuates metabolic adaptation if metabolic adaptation isn’t occurring to a meaningful degree in either group. It’s no surprise that these studies reported smaller magnitudes of weight loss, as they used shorter diet interventions and recruited leaner participants. Or, you might argue that Peos et al and Siedler et al used insufficient protocols, as their diet breaks were only one week long rather than two.

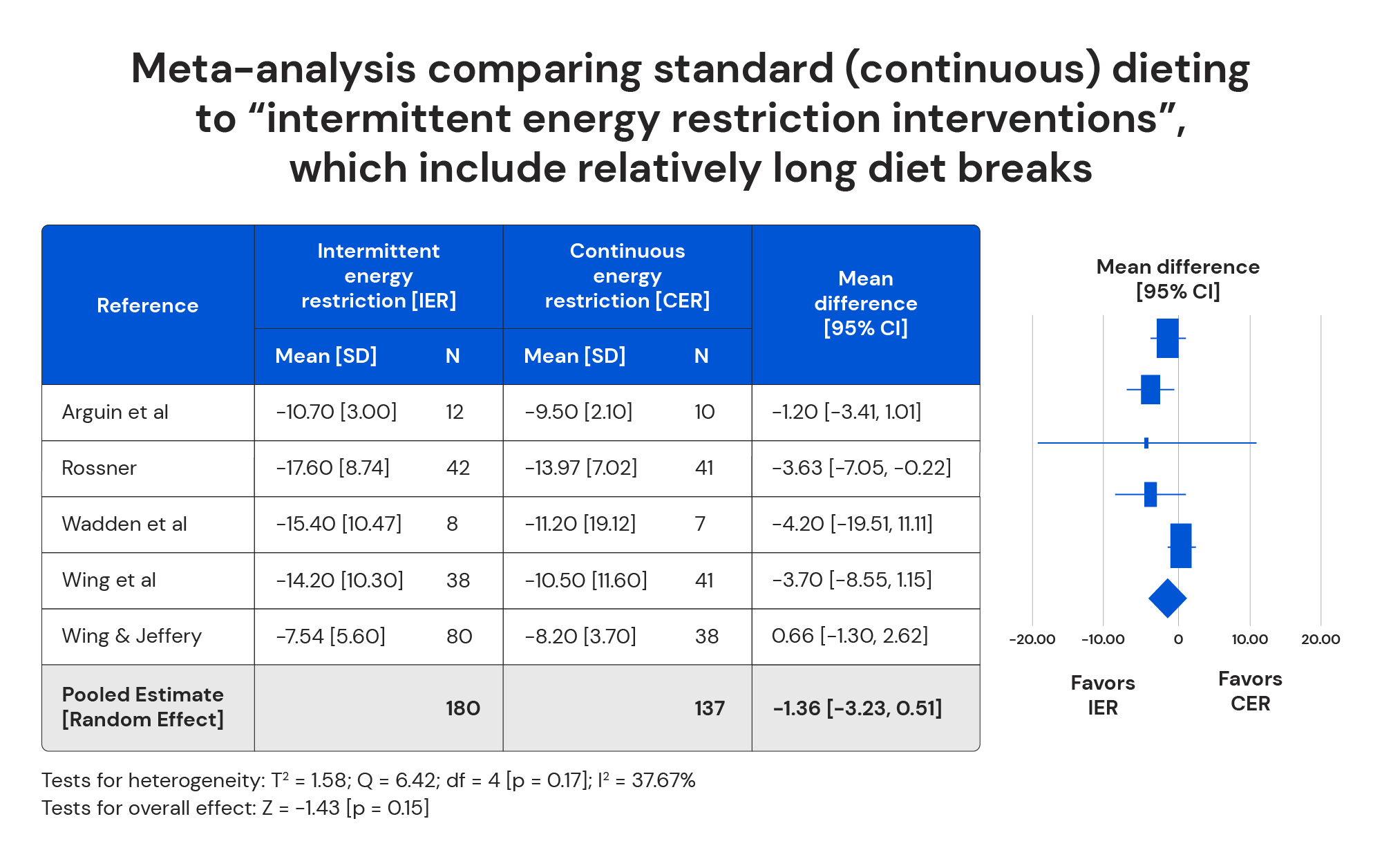

Having said that, there are some other studies investigating a variety of “intermittent energy restriction” protocols that involve diet breaks lasting more than a week in duration. This literature was summarized in a meta-analysis by Harris and colleagues, which was published in 2018. As shown in Figure 9, results indicated that “intermittent energy restriction interventions,” which include relatively long diet breaks, led to a fairly negligible weight loss advantage that was not statistically significant. It’s interesting to note that diet breaks led to larger weight loss advantages in studies with larger amounts of total weight loss, which might reinforce the idea that diet breaks only have an impact in the context of larger weight loss interventions (i.e., when individuals are aiming to lose at least ~15kg of body mass). Nonetheless, the totality of the research provides insufficient evidence to suggest that diet breaks are “better” than a standard weight loss approach.

Are Refeeds and Diet Breaks Useless?

I was fairly optimistic about diet breaks and refeeds when I first started publishing metabolic adaptation research in 2014, and my cautious optimism persisted when I revisited the topic in a 2020 paper. Nonetheless, in light of the most recent research, it’s hard to confidently suggest that refeeds or diet breaks will meaningfully attenuate metabolic adaptation or impact energy expenditure for the vast majority of people. If any metabolic advantage does exist, it appears to be restricted to specific scenarios where substantial metabolic adaptation occurs (such as very large magnitudes of weight loss or extreme levels of leanness), and seems more likely with longer (≥2 weeks) diet breaks rather than one-week diet breaks or shorter refeeds. We can’t necessarily rule out the possibility of a context-dependent metabolic effect in extreme dieting scenarios, but even if this effect does exist, it would be quite small and inaccessible to the vast majority of dieters. In addition, the potential benefits must be weighed against the obvious downside, which is that it takes a much longer time to reach a weight loss goal when relatively long diet breaks are utilized.

Nonetheless, failing to prevent or attenuate metabolic adaptation wouldn’t necessarily make refeeds and diet breaks entirely useless. The available research seems to suggest that diet breaks confer some modest benefits related to hunger management and psychological outcomes, which might improve dietary adherence or make weight loss diets slightly more tolerable. As noted previously, the 2018 study by Byrne and colleagues implies that diet breaks facilitated weight loss, primarily by enhancing dietary adherence. The studies by Peos et al and Siedler et al collectively hinted at small but beneficial impacts on hunger, appetite, desire to eat, and dietary disinhibition. Peos and colleagues also reported modest improvements in muscular endurance after diet breaks, as well as higher self-reported alertness and lower levels of irritability. In addition, the previously discussed study by Campbell and colleagues also reported results that leaned slightly (but inconclusively) in favor of better fat-free mass retention when using refeeds.

So, it would be incorrect to definitively assert that refeeds or diet breaks prevent, or even attenuate metabolic adaptation. However, it would also be incorrect to definitively assert that refeeds and diet breaks are entirely useless. They won’t supercharge your metabolism, but there are other defensible reasons to give them a try if you’re interested.

How to Implement Refeeds Within MacroFactor

If you’re interested in implementing refeeds within MacroFactor, there are three easy ways to do it.

First, you could simply do it, and opt not to change any settings at all. MacroFactor is adherence-neutral, and responds to what you actually did, rather than what your targets were supposed to be. You could simply choose 1-3 days throughout the week to increase your calorie and carbohydrate intake, track your intakes accurately, and MacroFactor will roll with the punches and continue to adjust without any unfavorable impacts on app function.

If you’re on a coached program, a second approach involves using the “shift calories” option during program set-up. This allows you to shift calories to modestly increase calorie targets on specific days (while reducing them on others), which often accomplishes what many refeeders are looking for.

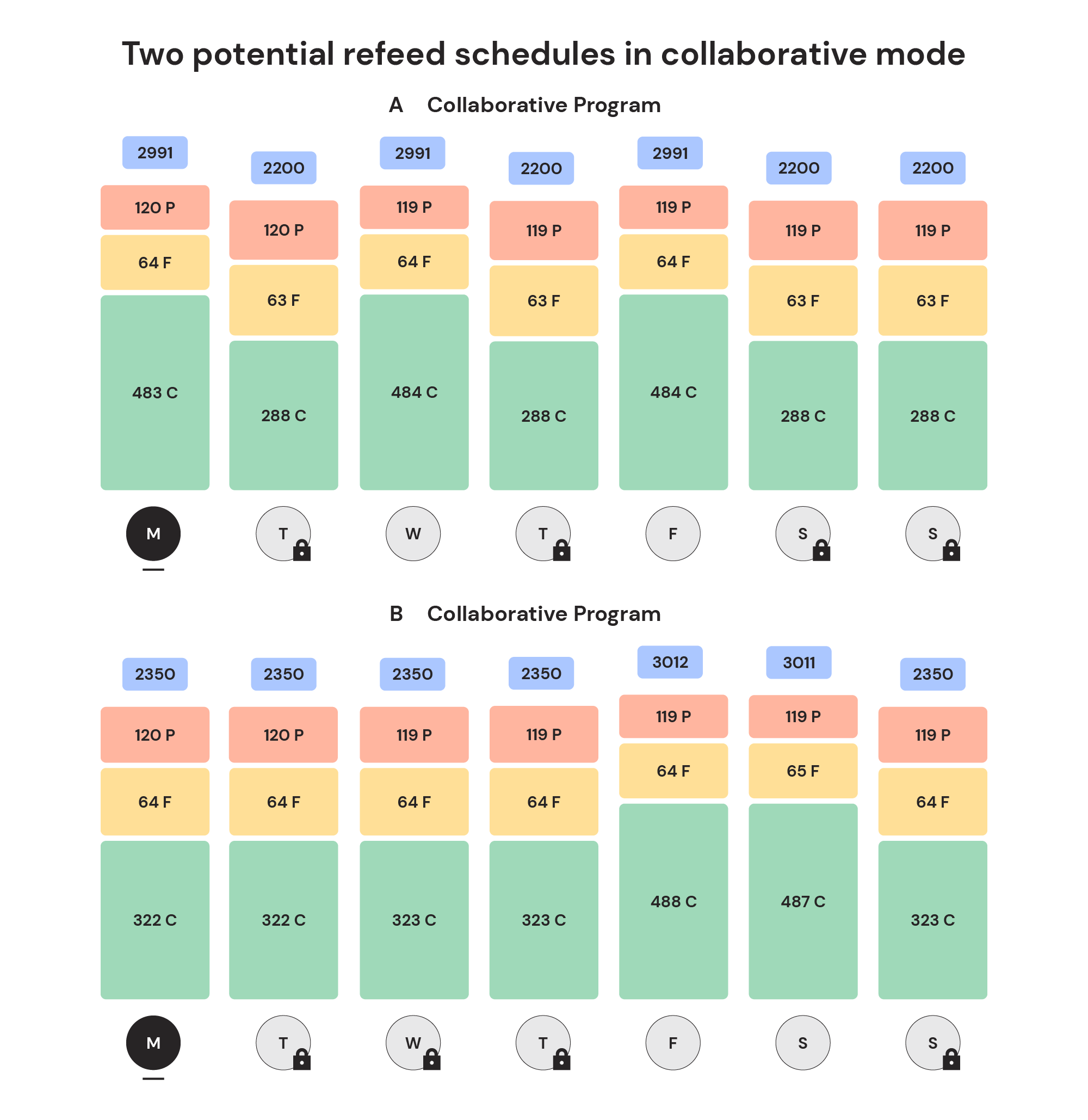

Alternatively, if you’re looking for a little more control and customization for your refeed protocol, you could choose to operate the app in collaborative mode (or manual mode) rather than coached mode. Collaborative mode is designed to give you the freedom to adjust calorie, carb, fat, and protein targets on a day-to-day basis within your macro plan, all while keeping you on track with your weekly calorie target. This functionality is perfectly suited to enable just about any refeed strategy you’d be interested in applying, even if your refeed days differ week-to-week. For example, you could decide to have higher carbs (and calories) on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday to accommodate your training schedule (Figure 10A), or to have higher carbs (and calories) on Friday and Saturday to accommodate your social schedule (Figure 10B).

Manual mode offers maximal flexibility for setting completely customized day-to-day nutrition targets, so it’s also perfectly suited for a wide range of refeed strategies. Just note that MacroFactor’s coaching algorithms will adjust your weekly energy budget to keep you on track toward your goals in collaborative mode, but not manual mode.

How to Implement Diet Breaks Within MacroFactor

As is the case for refeeds, diet breaks can also be very easily accommodated in MacroFactor.

First, you could simply implement diet breaks as you wish, without the need to change any settings at all. Due to the adherence-neutral nature of the MacroFactor algorithm and the continuously updating energy expenditure estimate on your dashboard, diet breaks are a breeze. To implement a diet break, you could simply increase your calorie intake to approximately match your current energy expenditure estimate for a week or two (or more). After this diet break period, you could go right back to aiming for the nutrition targets associated with your weight loss goal.

Alternatively, you could edit your goal to “maintenance” for a week or two (or more), then switch back to your original weight loss goal when you’re done with the diet break. Some users might have reservations about switching their goal due to concerns about losing data, breaking tracking streaks, or resetting the expenditure algorithm. Fortunately, these concerns are not applicable; MacroFactor maintains continuity when you switch goals, so you don’t lose anything by temporarily shifting to maintenance for a couple weeks, then shifting right back to your original goal.

Conclusions

There was once a time where refeeds and diet breaks were viewed as a potential solution to stop metabolic adaptation in its tracks. With this in mind, there is good news and bad news. The bad news is that refeeds and diet breaks don’t seem to meaningfully impact fat loss or energy expenditure in most common diet scenarios. However, the good news is that we don’t necessarily need a foolproof antidote to metabolic adaptation, as it doesn’t seem to be very predictive of successful weight loss outcomes. Metabolic rate aside, dieters might be interested in refeed and diet break strategies for other potential benefits related to hunger management, dietary adherence, maintenance of exercise performance while dieting, or a more tolerable dieting experience. Whatever your reasons for exploring refeeds or diet breaks happen to be, MacroFactor makes these strategies easy to implement en route to your goals.